Like movies, our own history has plot twists. Thanks to some of the notable spies that contributed to how history is told today. In this article, we list down the ten of the most notable atomic spies in history that could be the inspiration for one of your favorite espionage movies or books.

Here are the ten most notable atomic spies in olden times.

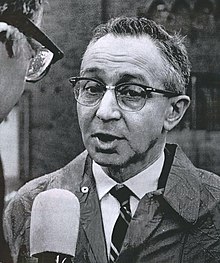

- Morris Cohen

Morris Cohen was born on July 2, 1910, to a Jewish immigrant family in Harlem, New York City. Cohen was recruited into the United States Army in mid-1942. Army and was stationed in Europe. In November 1945, he was dismissed from the Army and emigrated to the United States, where he resumed his Soviet Union espionage job. In 1945, the Cohens gave precise plans for the nuclear explosion to Moscow, among other things. Interaction with Soviet intelligence was momentarily cut off during this time because to the compromise of Soviet spy networks, but it was reestablished in 1948 when the Rezidentura determined that Cohen could be contacted. They ensured the continuous secret communication with a number of the Rezidentura’s most valued sources with the help of Lona Cohen. They started working with Colonel Rudolph Abel in the United States until 1950, when they surreptitiously left the country and relocated to Lublin, Poland. Morris and Lona traveled to Japan, Hong Kong, Australia, New Zealand, Austria, Belgium, and the Netherlands on behalf of the Soviet Union during their time in Poland. On January 7, 1961, British security officers arrested the Cohens for their involvement in the Portland Spy Ring, a Soviet espionage operation that had infiltrated the Royal Navy. They were found guilty of Soviet Union espionage and sentenced to ten years in prison. Because they were part of a prisoner swap, Morris and Lona spent eight years in prison.

Morris Cohen was born on July 2, 1910, to a Jewish immigrant family in Harlem, New York City. Cohen was recruited into the United States Army in mid-1942. Army and was stationed in Europe. In November 1945, he was dismissed from the Army and emigrated to the United States, where he resumed his Soviet Union espionage job. In 1945, the Cohens gave precise plans for the nuclear explosion to Moscow, among other things. Interaction with Soviet intelligence was momentarily cut off during this time because to the compromise of Soviet spy networks, but it was reestablished in 1948 when the Rezidentura determined that Cohen could be contacted. They ensured the continuous secret communication with a number of the Rezidentura’s most valued sources with the help of Lona Cohen. They started working with Colonel Rudolph Abel in the United States until 1950, when they surreptitiously left the country and relocated to Lublin, Poland. Morris and Lona traveled to Japan, Hong Kong, Australia, New Zealand, Austria, Belgium, and the Netherlands on behalf of the Soviet Union during their time in Poland. On January 7, 1961, British security officers arrested the Cohens for their involvement in the Portland Spy Ring, a Soviet espionage operation that had infiltrated the Royal Navy. They were found guilty of Soviet Union espionage and sentenced to ten years in prison. Because they were part of a prisoner swap, Morris and Lona spent eight years in prison.

- Klaus Fuchs

Fuchs, a German-born physicist, moved to England in 1933 when Nazism rose to power in Germany, and became a British citizen in 1942. He had previously offered to spy for the Soviets at that point. Fuchs joined a group of British scientists who traveled to Los Alamos to work on the Manhattan Project in late 1943, and he later passed on crucial information on atomic weapons design to the Soviets, allowing them to speed up their nuclear research. Fuchs confessed in early 1950 after encrypted cables exposed his espionage. Authorities tracked down Harry Gold, a key courier for other Los Alamos spies, thanks to his evidence.

Fuchs, a German-born physicist, moved to England in 1933 when Nazism rose to power in Germany, and became a British citizen in 1942. He had previously offered to spy for the Soviets at that point. Fuchs joined a group of British scientists who traveled to Los Alamos to work on the Manhattan Project in late 1943, and he later passed on crucial information on atomic weapons design to the Soviets, allowing them to speed up their nuclear research. Fuchs confessed in early 1950 after encrypted cables exposed his espionage. Authorities tracked down Harry Gold, a key courier for other Los Alamos spies, thanks to his evidence.

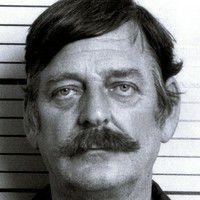

- Harry Gold

Harry Gold, born Henrich Golodnitsky on December 11, 1910, was a Swiss-born American laboratory chemist who was convicted as a courier for the Soviet Union during World War II for passing atomic secrets from Klaus Fuchs, an identified Soviet Union agent. Gold’s confession outlined several other people linked to the espionage network, and led to the arrest of David Greenglass. Gold appeared as a government witness in the conviction of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were tried and executed for their roles in the scandal in 1953. He was sentenced to 15 years in bars. Gold was brought back to Philadelphia. He was a clinical chemist at John F. Kennedy Memorial Hospital’s pathology lab, eventually working for the chief pathologist. At the age of 61, he died on August 28, 1972, during heart surgery.

Harry Gold, born Henrich Golodnitsky on December 11, 1910, was a Swiss-born American laboratory chemist who was convicted as a courier for the Soviet Union during World War II for passing atomic secrets from Klaus Fuchs, an identified Soviet Union agent. Gold’s confession outlined several other people linked to the espionage network, and led to the arrest of David Greenglass. Gold appeared as a government witness in the conviction of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were tried and executed for their roles in the scandal in 1953. He was sentenced to 15 years in bars. Gold was brought back to Philadelphia. He was a clinical chemist at John F. Kennedy Memorial Hospital’s pathology lab, eventually working for the chief pathologist. At the age of 61, he died on August 28, 1972, during heart surgery.

- David Greenglass

David Greenglass is a U.S. attorney. Before being assigned to Los Alamos in 1944, he worked as a machinist at the classified nuclear plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Greenglass was recruited to spy for the Soviets by his brother-in-law, Julius Rosenberg, in mid-1945, and gave material to the Soviets including a hand-drawn sketch and notes outlining the implosion-type weapon. Greenglass named his sister, Ethel Rosenberg, as the typer of the notes provided to the Soviets in his 1950 confession. Because of his cooperation, he received a reduced sentence and Ruth was granted immunity. The Rosenbergs were convicted and executed in June 1953, largely because of the Greenglasses’ evidence.

- Theodore Hall

Theodore Hall, the youngest physicist on the Manhattan Project, was the long-suspected third spy (after Fuchs and Greenglass) at Los Alamos, according to the decrypted Venona intercepts released in the mid-1990s. Hall, codenamed “Mlad,” contacted the Soviets in late 1944 and provided them with a critical update on the plutonium bomb’s development. Hall’s spying activities had been discovered by the FBI in the early 1950s, but without a confession, the FBI had no choice but to let him go rather than divulge the Venona project to the Soviets. Hall eventually relocated to the United Kingdom, where he established himself as a pioneer in biological research.

Theodore Hall, the youngest physicist on the Manhattan Project, was the long-suspected third spy (after Fuchs and Greenglass) at Los Alamos, according to the decrypted Venona intercepts released in the mid-1990s. Hall, codenamed “Mlad,” contacted the Soviets in late 1944 and provided them with a critical update on the plutonium bomb’s development. Hall’s spying activities had been discovered by the FBI in the early 1950s, but without a confession, the FBI had no choice but to let him go rather than divulge the Venona project to the Soviets. Hall eventually relocated to the United Kingdom, where he established himself as a pioneer in biological research.

- George Koval

In Sioux City, Iowa, Koval was birthed to Russian Jewish immigrants. He moved to the Soviet Union with his parents as an adult, settling in the Jewish Autonomous Region near the Chinese border. The GRU recruited Koval, trained him, and gave him the secret name DELMAR. In 1940, he returned to the United States and was drafted into the United States Army. Early in 1943, the army was formed. According to the Russian government, Koval worked in atomic research facilities and conveyed information to the Soviet Union about the production procedures and volumes of polonium, plutonium, and uranium used in American atomic armament, as well as details of weapon production sites. Koval took a trip to Europe in 1948 but never returned to the United States. For his service, Russian President Vladimir Putin honored Koval the Hero of the Russian Federation insignia posthumously in 2007.

In Sioux City, Iowa, Koval was birthed to Russian Jewish immigrants. He moved to the Soviet Union with his parents as an adult, settling in the Jewish Autonomous Region near the Chinese border. The GRU recruited Koval, trained him, and gave him the secret name DELMAR. In 1940, he returned to the United States and was drafted into the United States Army. Early in 1943, the army was formed. According to the Russian government, Koval worked in atomic research facilities and conveyed information to the Soviet Union about the production procedures and volumes of polonium, plutonium, and uranium used in American atomic armament, as well as details of weapon production sites. Koval took a trip to Europe in 1948 but never returned to the United States. For his service, Russian President Vladimir Putin honored Koval the Hero of the Russian Federation insignia posthumously in 2007.

- Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

Ethel Rosenberg and Julius Rosenberg were American citizens convicted of spying for the Soviet Union. The pair was found guilty of passing on top-secret secrets concerning radar, sonar, jet engines, and key nuclear weapon designs. The US was the only state in the world with nuclear warheads at the time. They were convicted of espionage in 1951 and executed by the United States government in 1953 at the Sing Sing penitentiary facility in Ossining, New York, and became the first American nationals to be executed for such allegations.

Ethel Rosenberg and Julius Rosenberg were American citizens convicted of spying for the Soviet Union. The pair was found guilty of passing on top-secret secrets concerning radar, sonar, jet engines, and key nuclear weapon designs. The US was the only state in the world with nuclear warheads at the time. They were convicted of espionage in 1951 and executed by the United States government in 1953 at the Sing Sing penitentiary facility in Ossining, New York, and became the first American nationals to be executed for such allegations.

- Saville Sax

Sax was born in New York he lived with his grandfather in Manhattan. His parents are native Russians, of Jewish lineage. Saville met Soviet spies through his mother, Bluma, who worked with Russian War Relief, a Communist front organization. Sax used the alias “Oldster” and traveled to New Mexico on a regular basis to gather information from Hall. Boria Sax was Saville’s son, Sarah Sax was her daughter, and Anne Saville Arenberg was Saville’s sister (1925-1967). Saville ended up teaching values clarification in a Great Society-funded education program called NEXTEP. When he was an adult hippie, untidy in his personal habits and addicted to lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD, and other hallucinogenic substances, and openly boasted of his role in atomic spying. He died in Edwardsville, Illinois, on September 25, 1980.

Sax was born in New York he lived with his grandfather in Manhattan. His parents are native Russians, of Jewish lineage. Saville met Soviet spies through his mother, Bluma, who worked with Russian War Relief, a Communist front organization. Sax used the alias “Oldster” and traveled to New Mexico on a regular basis to gather information from Hall. Boria Sax was Saville’s son, Sarah Sax was her daughter, and Anne Saville Arenberg was Saville’s sister (1925-1967). Saville ended up teaching values clarification in a Great Society-funded education program called NEXTEP. When he was an adult hippie, untidy in his personal habits and addicted to lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD, and other hallucinogenic substances, and openly boasted of his role in atomic spying. He died in Edwardsville, Illinois, on September 25, 1980.

- Oscar Seborer

Klehr and John Earl Haynes confirmed the existence of a fourth Soviet spy at Los Alamos in 2019, after studying through freshly declassified FBI files. Oscar Seborer, nicknamed “Godsend,” was the son of Jewish immigrants from Poland who worked at Los Alamos from 1944 to 1946 as an electrical engineer. Seborer’s work on the wiring of the bomb’s explosive trigger would have given him access to different information than Fuchs and Hall, including critical intelligence regarding the implosion detonation method, though it’s still unclear what information he delivered to the Soviets.

Klehr and John Earl Haynes confirmed the existence of a fourth Soviet spy at Los Alamos in 2019, after studying through freshly declassified FBI files. Oscar Seborer, nicknamed “Godsend,” was the son of Jewish immigrants from Poland who worked at Los Alamos from 1944 to 1946 as an electrical engineer. Seborer’s work on the wiring of the bomb’s explosive trigger would have given him access to different information than Fuchs and Hall, including critical intelligence regarding the implosion detonation method, though it’s still unclear what information he delivered to the Soviets.

- Melita Norwood

Melita Norwood, 87, stands outside her home in Bexleyheath, England, in 1999 to give a statement about her involvement in providing atomic secrets to the KGB.

The Soviet Union’s longest-serving spy in Britain, served as a secretary for a Tube Alloys project director. Throughout the war—and into the 1970s—she gave information to Soviet operatives while living a seemingly regular life in the London suburbs. It’s unknown how much Norwood’s espionage aided the Soviet atomic program, but when she visited Moscow in 1979, she was publicly recognized for her efforts. When Norwood was finally caught as a spy in the 1990s, she “gladly confirmed what she had done and stated she would do it again,” according to Harvey Klehr, retired professor of politics and history at Emory University and author of several books on Soviet espionage.

These real-life spies are some of the authors of our written history today. Their acts could be destructive or beneficial at some point, but these people are notable for being competent with skills and attributes of being a strong critical thinker, good at communication, logical thinkers, and having a love of cryptography puzzles.