Despite what the movies tell us, dinosaurs probably didn’t roar at their prey. It’s more likely that they chirped like birds, based on a well-preserved new fossil with an intact voice box.

A team of researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences discovered an almost-complete skeleton of a new dinosaur species in northeastern China.

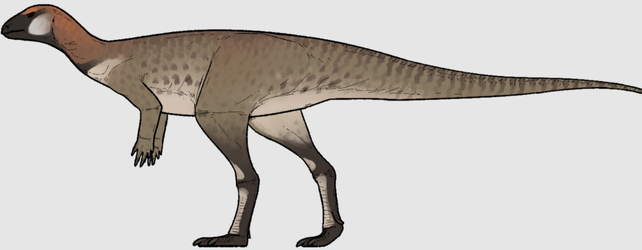

This two-legged, 72 centimeter (2.4 foot) long herbivore was named Pulaosaurus qinglong after Pulao, a tiny dragon from Chinese mythology that, the story goes, cries out loudly.

Related: The Raptor Noises in Jurassic Park Are Mating Tortoises

That namesake is no coincidence – Pulaosaurus is one of very few dinosaurs for which we have some idea of the noises it could have made.

That’s because the fossil is extremely well-preserved. Not only are most of the bones present and accounted for, but so are parts we don’t usually find, including structures in the larynx. There’s even some impressions of what could be its final meal visible in its gut.

Leaf-shaped, cartilaginous structures in the larynx are very similar to modern birds, the researchers write, which suggests that Pulaosaurus could have communicated through complex chirps and calls. Sadly, don’t expect to be able to listen to a reproduction any time soon.

“Due to the compression of the Pulaosaurus mandible, the exact width of the mandible is unknown, so acoustic calculations of Pulaosaurus cannot be made,” the researchers write.

Finding a fossilized larynx in a dinosaur is extremely rare – in fact, this is only the second time one has been identified. The other was in a very different type of dinosaur: an armored ankylosaur known as Pinacosaurus.

Intriguingly, these two examples are very distantly related and separated by about 90 million years of evolution. That means this kind of larynx structure could have been widespread among dinosaurs.

So why haven’t we found more? The team suggests that either these fragile structures don’t fossilize very often, or perhaps they’re being mistakenly classified as other parts of the throat.

“Reanalysis of vocal anatomy within non-avian dinosaurs needs to be carried out to assess the accuracy of identification among curated specimens,” the researchers write.

Maybe with more examples we’ll get a better understanding of how dinosaurs really sounded.

The research was published in the journal PeerJ.