The Model Context Protocol (MCP) and Agent-to-Agent (A2A) have gained a significant industry attention over the past year. MCP first grabbed the world’s attention in dramatic fashion when it was published by Anthropic in November 2024, garnering tens of thousands of stars on GitHub within the first month. Organizations quickly saw the value of MCP as a way to abstract APIs into natural language, allowing LLMs to easily interpret and use them as tools. In April 2025, Google introduced A2A, providing a new protocol that allows agents to discover each other’s capabilities, enabling the rapid growth and scaling of agentic systems.

Both protocols are aligned with the Linux Foundation and are designed for agentic systems, but their adoption curves have differed significantly. MCP has seen rapid adoption, while A2A’s progress has been more of a slow burn. This has led to industry commentary suggesting that A2A is quietly fading into the background, with many people believing that MCP has emerged as the de-facto standard for agentic systems.

How do these two protocols compare? Is there really an epic battle underway between MCP and A2A? Is this going to be Blu-ray vs. HD-DVD, or VHS vs. Betamax all over again? Well, not exactly. The reality is that while there is some overlap, they operate at different levels of the agentic stack and are both highly relevant.

MCP is designed as a way for LLMs to understand what external tools are available to it. Before MCP, these tools were exposed primarily through APIs. However, raw API handling by an LLM is clumsy and difficult to scale. LLMs are designed to operate in the world of natural language, where they interpret a task and identify the right tool capable of accomplishing it. APIs also suffer from issues related to standardization and versioning. For example, if an API undergoes a version update, how would the LLM know about it and use it correctly, especially when trying to scale across thousands of APIs? This quickly becomes a show-stopper. These were precisely the problems that MCP was designed to solve.

Architecturally, MCP works well—that is, until a certain point. As the number of tools on an MCP server grows, the tool descriptions and manifest sent to the LLM can become massive, quickly consuming the prompt’s entire context window. This affects even the largest LLMs, including those supporting hundreds of thousands of tokens. At scale, this becomes a fundamental constraint. Recently, there have been impressive strides in reducing the token count used by MCP servers, but even then, the scalability limits of MCP are likely to remain.

This is where A2A comes in. A2A does not operate at the level of tools or tool descriptions, and it doesn’t get involved in the details of API abstraction. Instead, A2A introduces the concept of Agent Cards, which are high-level descriptors that capture the overall capabilities of an agent, rather than explicitly listing the tools or detailed skills the agent can access. Additionally, A2A works exclusively between agents, meaning it does not have the ability to interact directly with tools or end systems the way MCP does.

So, which one should you use? Which one is better? Ultimately, the answer is both.

If you are building a simple agentic system with a single supervisory agent and a variety of tools it can access, MCP alone can be an ideal fit—as long as the prompt stays compact enough to fit within the LLM’s context window (which includes the entire prompt budget, including tool schemas, system instructions, conversation state, retrieved documents, and more). However, if you are deploying a multi-agent system, you will very likely need to add A2A into the mix.

Imagine a supervisory agent responsible for handling a request such as, “analyze Wi-Fi roaming problems and recommend mitigation strategies.” Rather than exposing every possible tool directly, the supervisor uses A2A to discover specialized agents—such as an RF analysis agent, a user authentication agent, and a network performance agent—based on their high-level Agent Cards. Once the appropriate agent is selected, that agent can then use MCP to discover and invoke the specific tools it needs. In this flow, A2A provides scalable agent-level routing, while MCP provides precise, tool-level execution.

The key point is that A2A can—and often should—be used in concert with MCP. This is not an MCP versus A2A decision; it is an architectural one, where both protocols can be leveraged as the system grows and evolves.

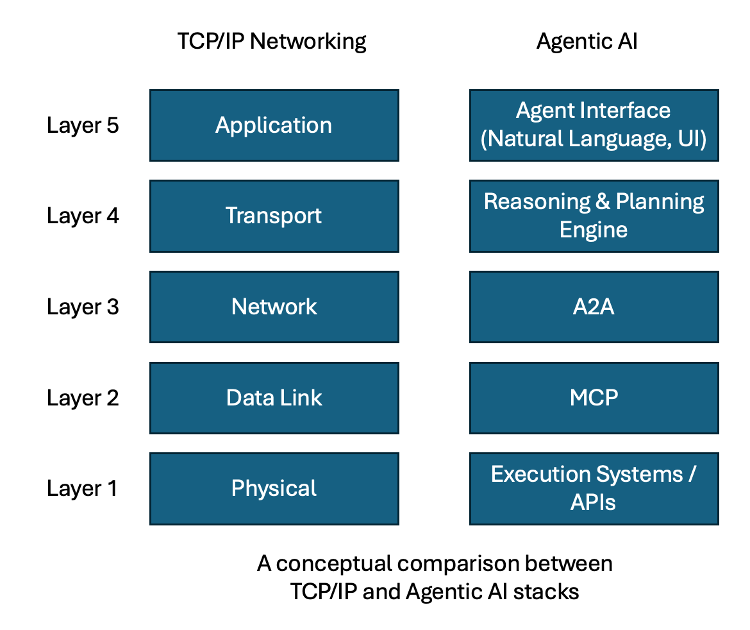

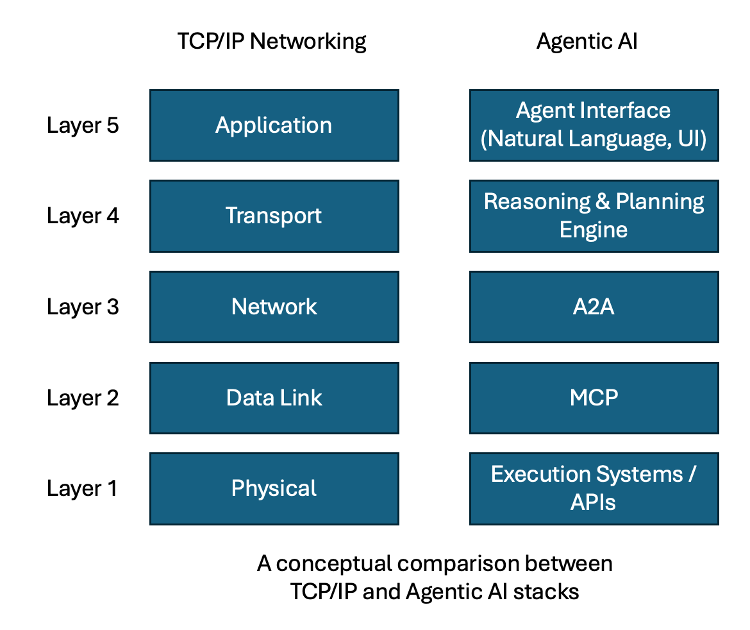

The mental model I like to use comes from the world of networking. In the early days of computer networking, networks were small and self-contained, where a single Layer-2 domain (the data link layer) was sufficient. As networks grew and became interconnected, the limits of Layer-2 were quickly reached, necessitating the introduction of routers and routing protocols—known as Layer-3 (the network layer). Routers function as boundaries for Layer-2 networks, allowing them to be interconnected while also preventing broadcast traffic from flooding the entire system. At the router, networks are described in higher-level, summarized terms, rather than exposing all the underlying detail. For a computer to communicate outside of its immediate Layer-2 network, it must first discover the nearest router, knowing that its intended destination exists somewhere beyond that boundary.

This maps closely to the relationship between MCP and A2A. MCP is analogous to a Layer-2 network: it provides detailed visibility and direct access, but it does not scale indefinitely. A2A is analogous to the Layer-3 routing boundary, which aggregates higher-level information about capabilities and provides a gateway to the rest of the agentic network.

The comparison may not be a perfect match, but it offers an intuitive mental model that resonates with those who have a networking background. Just as modern networks are built on both Layer-2 and Layer-3, agentic AI systems will eventually require the full stack as well. In this light, MCP and A2A should not be thought of as competing standards. In time, they will likely both become critical layers of the larger agentic stack as we build increasingly sophisticated AI systems.

The teams that recognize this early will be the ones that successfully scale their agentic systems into durable, production-grade architectures.