By Max Papier.

Italian tailoring is a wide term, and it encompasses far more than most people initially expect. Over the course of my career, I’ve been fortunate enough to try tailoring from across Italy in an attempt to understand which style made sense for me – not just aesthetically, but practically.

The way I’ve come to understand Italian tailoring is through its cities. This is, of course, a simplification, but in my experience the regional differences in Italian tailoring do mirror some of the character of the places themselves. Geography, history and temperament all leave their mark on how a jacket is conceived and worn.

For someone beginning their journey, this city-by-city approach could serve as a useful guide – not to prescribe taste, but to help clarify instinct.

There are, of course, other tailoring centres in Italy – Rome perhaps chief among them – but for me, Milan, Naples, and Florence form the clearest emotional and stylistic triangle.

Milan: Structure, discipline, intent

Start in the north, with Milan. Historically Italy’s business capital, Milan is formal, efficient, and pragmatic. Having been heavily bombed during the Second World War, much of the city was rebuilt quickly in the post-war years, resulting in an urban landscape that often feels modern, functional and restrained.

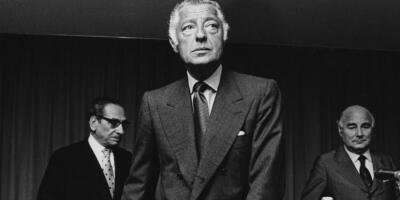

Milanese tailoring reflects this sensibility closely. Jackets are structured and purposeful, with strong shoulders, clean front darts and a sense of visual authority (above). Think of mid-20th-century Italian industrialists – Gianni Agnelli, Luca di Montezemolo, Vittorio Valletta – men who needed their clothes to project clarity and command.

Among Italian styles, Milan sits closest to English tailoring in both appearance and intent. It is ideal for someone whose days are spent in formal environments, or who prefers tailoring that communicates decisiveness rather than ease.

“I’m not sure where it comes from but we have these strong shoulders on our suits which I love,” says Nicoletta Caraceni. “It gives them power, presence, while the rest of the jacket can be sharp but quite lightweight.”

Naples: Movement, ease, expression

At the other end of the country lies Naples – a city of contradictions. Chaotic, beautiful and unapologetically alive, it exists in the shadow of an active volcano and beside the sea. Life there feels warmer, looser, and less restrained.

Neapolitan tailoring dispenses with rigidity. Heavy padding gives way to spalla camicia shoulders, lighter canvassing and expressive front darts that often run past the hip pocket to the hem. The trousers tend to be slimmer, more athletic. (Elia Caliendo above, with Simon.)

It’s no coincidence that many people gravitate toward Neapolitan jackets when they want something to wear with denim or chinos. The style is inherently casual, built to accommodate the body rather than impose upon it.

Filmmaker Gianluca Migliarotti – who grew up in Naples but who now lives in Milan – has talked about this in the past. In his words, “Neapolitans tend to enjoy life in a chaotic and hedonistic way, which makes everything more interesting – sexier, more playful. Less precise, perhaps, and in most cases, far from immaculate.”

Roman tailoring often seems like a dialogue between Milan and Naples. The shoulder retains the clarity and discipline of the north, but softened – less rigid, more forgiving. And you see more colour slipping in: Roman tailoring is often a little flashier and brighter than Milan, without tipping into Neapolitan exuberance.

An interesting example is the difference between the two Caraceni houses in Milan, and T&G Caraceni in Rome (above). They share the same lineage, but the Roman cut is a little gentler in the shoulder, slightly rounder through the chest, and more accommodating to the body.

Permanent Style reader Andrew Borda has commented on this in the past in his articles, having been a customer of Ferdinando Caraceni in Milan and now moved to T&G in Rome. “The Ferdinando jacket has a bit of a ‘stronger’ and more dramatic look,” he says. “There are more pronounced shoulders, a bit more drape, slightly more belly on the lapels, and it can have the tendency to look a bit boxy.”

Florence: Balance, restraint, continuity

Situated in the centre of the country, Florence feels – at least to me – like a balance between north and south. The birthplace of the Renaissance, it is a city shaped by artists rather than industrialists, but is surrounded by countryside rather than factories or coastline. That rural context matters.

“Florence is a town in the countryside,” Florentine Tommaso Capozzoli has told Simon in the past. “The colours are those of the country, and the jacket is tough, made to be lived in.” That’s why you have strong edge stitches and often swelled edges, to protect the edges over many years of wear.

Florentine tailoring has always felt grounded to me, both literally and aesthetically. There is an emphasis on natural, subdued colors drawn from the landscape: browns, tans, creams, olives – shades that feel worn-in rather than attention-seeking. These are garments designed to live quietly alongside their wearer, rather than announce themselves.

That philosophy carries through to the cut and the finishing. The shoulder is typically unpadded, but finished with a cleanliness closer to Milan than Naples. The familiar front dart found in both Milanese and Neapolitan jackets disappears entirely, replaced by an angled side dart hidden behind the sleeve – preserving the integrity of the cloth and pattern. Breaking up a check would be unthinkable (below).

The clothes are not meant to be fancy, and so they avoid fancy gestures. You don’t see ornamental Milanese buttonholes, nor the double rows of pick-stitching or the bright, expressive linings often associated with Naples. Florentine tailoring is intentionally restrained. Waist suppression comes from careful ironing and that concealed side dart, creating a silhouette that feels natural rather than engineered.

Where Milan gravitates toward boardroom greys and navies, and Naples leans into vivid blues and sun-faded colors, Florence prefers earth tones and understatement. It brings to mind Dieter Rams’ idea that good design is as little design as possible.

For me, Florence was where things finally clicked.

Finding your fit

Understanding how these traditions survive – or disappear – helps explain not just how the clothes look, but why they may or may not suit the life you’re trying to dress.

No single region of tailoring is ever going to suit every situation. Each excels at something specific, and understanding that is part of the pleasure.

Milanese tailoring will almost always make you look more heroic. The structure, the shoulder, the clarity of line – these are clothes that project authority and confidence, and they do so exceptionally well. Neapolitan tailoring, by contrast, will likely always be easier to pair with denim, knitwear, and other casual pieces. It thrives in movement and informality, and it feels most at home when things are a little relaxed.

If you’re looking for something more honest – something that sits quietly in between – it may be worth trying Florence. Florentine tailoring doesn’t try to make you look bigger, sharper, or more flamboyant than you are. Instead, it aims for balance: clothes that feel appropriate across a wide range of contexts without demanding attention.

For someone beginning their journey into Italian tailoring, I don’t think the choice isn’t about right or wrong. It’s about lifestyle and personality. Are your days spent in boardrooms, or do you move fluidly between formal and informal worlds? Do you want your clothes to assert themselves, or to quietly support the way you live?

In my case, the answer was always somewhere in between.

That is why Florence became the place where I found my fit – not just in the cut of a jacket, but in the values behind it. For me, that is where the soul of Florentine tailoring truly lives.

Max Papier (above) is based in New York and has spent the past decade commissioning bespoke clothing from Italian tailors, particularly in Florence. He will expand on these personal experiences in upcoming articles.