Every second of every day, wherever a river empties into the sea, energy vanishes. The freshwater and saltwater collide, their salt concentrations equalise, and the chemical potential that existed between them dissipates as waste heat. No turbine captures it. No grid carries it away. Globally, this invisible haemorrhage amounts to roughly 2,400 gigawatts of continuously squandered power, enough to rival the world’s entire electricity consumption.

Researchers have known about this untapped reservoir since the 1950s, and they have a name for it: blue energy. The concept is disarmingly simple. Separate salty water from fresh with a membrane that lets only certain ions through, and the resulting charge imbalance generates voltage, much like a battery. But decades of effort have run into an annoying trade-off: membranes that allow ions to flow quickly tend to be poor at sorting them, while highly selective ones throttle the current.

Now a team at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL) has found an elegant workaround, borrowing a trick from the cells in your own body. Yunfei Teng, Tzu-Heng Chen and colleagues in Aleksandra Radenovic’s Laboratory of Nanoscale Biology coated the insides of tiny silicon-based nanopores with lipid bilayers, the same fatty double-layered membranes that wrap every living cell. Published today in Nature Energy, their results suggest this biological lubrication could push blue energy closer to something engineers might actually want to build.

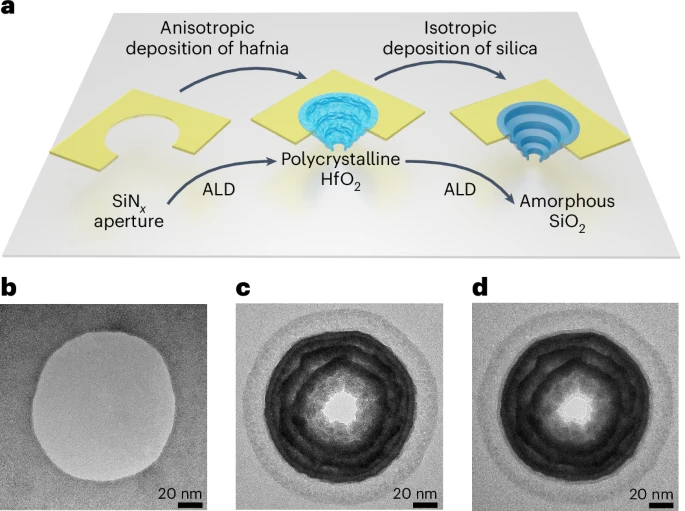

The problem they were tackling is a subtle one. Solid-state nanopores, drilled into robust materials like hafnium oxide using semiconductor fabrication methods, give you exquisite control over pore geometry. You can make them exactly 25 nanometres across and pack hundreds of millions into a square centimetre. What you can’t easily control is how the liquid behaves once it gets inside.

Lipid bilayers change that equation in two ways at once. Their charged headgroups (the team used mixtures of DOTAP, a positively charged lipid, and DOPC, a neutral one) boost the surface charge density to values that dwarf what bare solid-state materials can manage. At a 75 per cent DOTAP mix, the charge density hit 0.4 coulombs per square metre, roughly double that of graphene or boron nitride nanotubes, materials that have been the darlings of the nanofluidics world for years. But here is the really clever bit. At such high charge densities, something called hydration lubrication kicks in. Charged surfaces in water trap an ultrathin film of water molecules, perhaps only a few molecules thick, that clings via electrostatic attraction and acts as a molecular lubricant. The phenomenon has been well documented in tribology studies on mica, where it produces friction coefficients below 0.0002, but nobody had deliberately exploited it to enhance osmotic energy harvesting before.

In conventional solid-state materials, charge and friction are locked in an antagonistic relationship: ramping up one tends to increase the other, because denser surface charges mean stronger electrostatic drag on the passing fluid. The lipid bilayer decouples them. Its hydration layer reduces wall friction even as the charged headgroups ramp up ion selectivity, and computer simulations the team ran showed that beyond a slip length of about 20 nanometres, fluid velocity at the pore wall actually exceeds that in the centre of the channel. That is a peculiar inversion of normal flow behaviour. It is also what drives the performance gains.

Getting lipid bilayers inside nanopores only 24 nanometres across is, as you might imagine, not straightforward. The group used electrically charged liposomes, spherical lipid bubbles around 100 nanometres in diameter, and drove them toward the pore openings using an applied voltage. Electrophoretic force and electroosmotic flow worked together to guide the liposomes into the stalactite-shaped nanostructures, where the tight confinement squeezed and collapsed them, spreading a single bilayer coating (about 4 nanometres thick on each side) across the inner walls. The team tracked it all in real time by monitoring changes in ionic current.

Scaled up to a membrane containing roughly 1,000 of these coated nanopores arranged in a hexagonal grid spanning 20 micrometres, the system delivered a power density of about 51 kilowatts per square metre when calculated from the active pore area alone. Under conditions mimicking a real river-meets-ocean scenario, the figure came in at around 41 kilowatts per square metre. Even normalised to the total membrane area, which includes the dead space between pores, the output reached roughly 15 watts per square metre; some two to three times what existing polymer membrane technologies achieve. “Our work brings together the strengths of two main approaches to osmotic energy harvesting,” says Radenovic: “polymer membranes, which inspire our high-porosity architecture; and nanofluidic devices, which we use to define highly charged nanopores.”

Those numbers need some context. The commercialisation benchmark for blue energy has long been pegged at around 5 watts per square metre, a threshold that polymer membranes have only recently and inconsistently cleared. Nanofluidic approaches have posted far higher figures from individual nanopores in lab demonstrations, sometimes thousands of watts per square metre, but scaling those results to usable membrane areas almost always erases the advantage. What is different here is that the EPFL team maintained competitive performance while working at membrane-scale porosity comparable to commercial filtration membranes. Chen described the advance as moving blue-energy research into what he called “a true design era,” where precise control over nanopore geometry and surface properties could reshape ion transport from the ground up.

There are caveats, naturally. The membrane area tested remains tiny, just 314 square micrometres, and the silicon nitride platform would be challenging to scale beyond wafer dimensions. The lipid coating is also reversible: exposure to ethanol strips it away, which is handy for testing multiple compositions on the same device but raises fair questions about long-term durability in a working power plant exposed to biofouling and fluctuating water chemistry. The team acknowledges these limitations and suggests the underlying principle could in future be transferred to substrates with clearer paths to industrial production.

Still, the work represents something of a conceptual shift for the field. Rather than hunting for ever-thinner or ever-more-exotic membrane materials, the EPFL approach layers biological functionality onto robust semiconductor scaffolds. It is a hybrid strategy that borrows the best of both worlds. As Teng noted, the enhanced transport driven by hydration lubrication is a universal mechanism, one that extends well beyond blue-energy devices into areas like fine chemical processing, energy storage and ionic computing. Wherever rivers meet the sea, that invisible energy continues to dissipate. Whether lipid-lined nanopores can eventually capture a meaningful fraction of it remains an open question, but for the first time, the physics of charge and friction are pulling in the same direction.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Thank you for standing with us!