Table of Contents

Chemotherapy is widely known to damage the lining of the intestines. While this side effect is often treated as a localized problem, the impact does not stop in the gut. Damage to the intestinal wall changes which nutrients are available to gut bacteria, forcing the microbial community to adjust in response.

Chemotherapy Alters Gut Bacteria and Their Metabolism

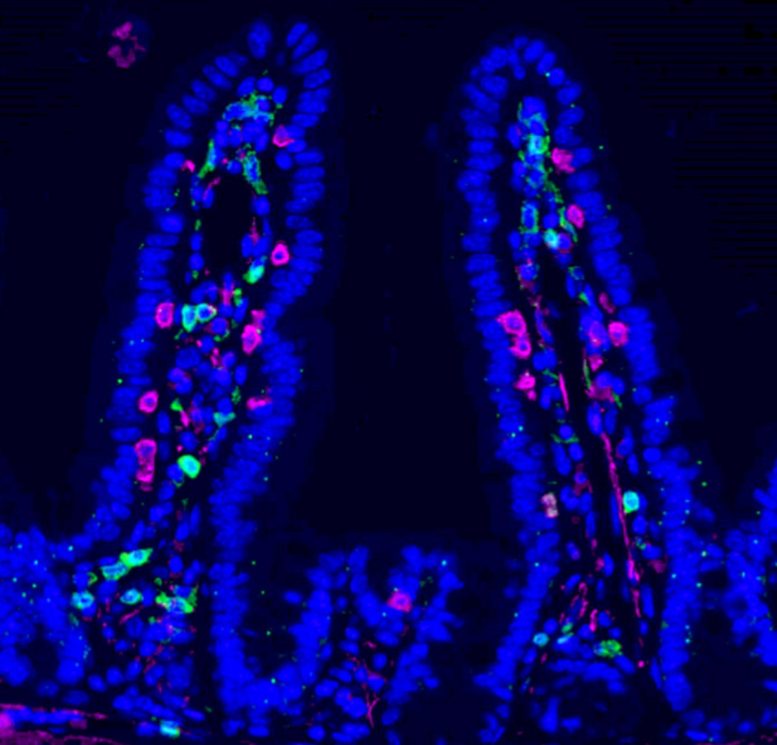

Researchers found that injury to the intestinal lining caused by chemotherapy reshapes the gut microbiome by altering its nutrient supply. As gut bacteria adapt, they increase production of indole-3-propionic acid (IPA), a compound derived from the amino acid tryptophan and produced by certain microbes.

A Gut Signal That Reaches the Immune System

IPA does not act only inside the digestive tract. Instead, it enters the bloodstream and travels to the bone marrow, where immune cells are formed. Once there, higher levels of IPA change how these immune cells develop. In particular, IPA reduces the production of immunosuppressive monocytes, cells that normally help tumors avoid immune attack and promote metastatic growth.

“We were surprised by how a side effect often seen as collateral damage of chemotherapy can trigger such a structured systemic response. By reshaping the gut microbiota, chemotherapy sets off a cascade of events that rewires immunity and makes the body less permissive to metastasis,” says Ludivine Bersier, first author of the study.

Stronger Immune Responses at Metastatic Sites

This shift in immune cell production leads to more active T cells and changes how immune cells interact within sites where cancer commonly spreads. The effect is especially pronounced in the liver. In preclinical models, these changes create an environment that is far less supportive of metastatic tumors.

Patient Data Support the Findings

The researchers also observed similar patterns in people undergoing cancer treatment. Clinical data were collected in collaboration with Dr. Thibaud Koessler (Geneva University Hospitals, HUG). Among patients with colorectal cancer, those who showed higher levels of IPA in the blood after chemotherapy also had lower levels of monocytes. This immune profile is linked to better survival outcomes.

“This work shows that the effects of chemotherapy extend far beyond the tumor itself. By uncovering a functional axis linking the gut, the bone marrow, and metastatic sites, we highlight systemic mechanisms that could be harnessed to durably limit metastatic progression,” says Tatiana Petrova, corresponding author of the study.

Long Lasting Effects and Future Directions

The study was supported by several organizations, including the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Swiss Cancer League. An ISREC Foundation Tandem Grant enabled close collaboration between clinical and basic research, led at Unil by Professor Tatiana Petrova and Dr. Thibaud Koessler at HUG. The researchers propose that chemotherapy can create a form of biological “memory,” driven by metabolites produced by gut microbes that continue to suppress metastatic growth over time.

Taken together, the findings point to a previously underrecognized gut–bone marrow–liver metastasis axis. This pathway helps explain how chemotherapy can produce lasting, bodywide effects and suggests new opportunities to use microbiome-derived molecules as supportive strategies to limit cancer spread.

Reference: “Chemotherapy-driven intestinal dysbiosis and indole-3-propionic acid rewire myelopoiesis to promote a metastasis-refractory state” by Ludivine Bersier, L. Francisco Lorenzo-Martin, Yi-Hsuan Chiang, Stephan Durot, Aleksander Czauderna, Tural Yarahmadov, Tania Wyss Lozano, Irena Roci, Jaeryung Kim, Nicola Zamboni, Nicola Vannini, Caroline Pot, Tinh-Hai Collet, Deborah Stroka, Jeremiah Bernier-Latmani, Matthias P. Lutolf, Simone Becattini, Thibaud Koessler and Tatiana V. Petrova, 15 December 2025, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-67169-7

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.