Katrina, Sandy, Andrew — some names are inextricably linked with some of the most devastating hurricanes in recent U.S. history. But how do hurricanes and other tropical storms get their names?

First, let’s start with how such storms are defined. Hurricanes are tropical cyclones with sustained winds of more than 74 mph (119 km/h) that develop east of the international date line. They are referred to as typhoons west of the international date line, and they’re called cyclones in the Indian Ocean and Australia. All are coordinated and named by a single body, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), which has a separate name list for typhoons.

To get a name, a storm must sustain winds of at least 39 mph (63 km/h) over a one-minute period. If it fails to do so, it receives a number instead of a name and is called a tropical depression.

The WMO also maintains a list of 21 storm names that it rotates every six years. The Atlantic storms list for 2025, for instance, specifies that Andrea and Barry are next in line, the same names of storms that last passed through the Atlantic in 2019. In the next hurricane season, the WMO will flip the genders of the names, alternating between them evenly, said Lourdes Avilés, associate provost at Plymouth State University and author of “Taken by Storm, 1938: A Social and Meteorological History of the Great New England Hurricane”a book (American Meteorological Society, 2013) about the history of hurricane naming.

If there are more than 21 named storms in a hurricane season, there is a backup list, which the WMO has had to use only twice, in 2005 and 2020. It used to be made of Greek letters (e.g., alpha, beta, gamma, delta, epsilon), but in 2020, the WMO replaced it with another list of supplemental names.

If a storm is particularly destructive, like hurricane Katrina or Fiona, the country where the hurricane made landfall can request that the WMO retire the name. The organization then votes on a new one to replace it, choosing a name that begins with the same letter of the alphabet. So, even if your name doesn’t appear on the list, there’s a chance that in a future WMO vote, your name could end up on it.

Your name is more likely to be associated with a famous storm or a hurricane if it begins with a letter between G and R, which lines up with June and August, when atmospheric conditions are optimal for producing tropical storms.

For example, hurricane Ian emerged as a tropical wave in the Caribbean on Sept. 23, 2022, before it became Tropical Depression Nine with sustained winds just below 39 mph (63 km/h). When it reached winds of 45 mph (72 km/h), it got the name Tropical Storm Ian, becoming the ninth named storm of the 2022 Atlantic hurricane season. Then, it intensified into a hurricane on Sept. 26, 2022, reaching Category 4 before hitting Florida and South Carolina days later. The U.S. asked the WMO to retire the name Ian, replacing it with Idris, which now appears on the list.

History of hurricane names

A tall, stammering meteorologist arrived at the 19th-century lecture hall with his papers falling around him. His name was Clement Wragge, though his colleagues often called him “Inclement.”

In the 19th century, Spanish sailors named storms after saints, according to hurricane historian Ivan R. Tannehill. Hurricane San Felipe hit the country in 1876, but another hurricane of the same name appeared in 1928. The Spanish also had a problem when two tropical storms happened on the same day, however.

Wragge had a solution to this problem: He would refer to northern storms after local politicians he disliked, joking that the officials were “causing great distress” or “wandering aimlessly about the Pacific” when a tropical storm came calling.

“This is a convention we ought to consider bringing back,” joked Kerry Emanuel, a professor of meteorology at MIT and author of “Divine Wind: The History and Science of Hurricanes (Oxford University Press, 2005).

For the southern storms, Wragge started naming them after figures from Greek and Roman mythology. But when he ran out, he moved on to naming them after Pacific Island women who had caught his eye. He is today credited as the first meteorologist to begin naming storms after women, according to Tannehill.

During World War II, U.S. pilots picked up Wragge’s naming practices. The Air Force began naming tropical cyclones after their grandmas, wives and girlfriends back home. “There were, like, multiple hurricanes called Carol and things like that,” Avilés said. “[It was used] in both ways to honor and to be sexist against women.”

Later, scientists worried that gendering hurricanes might have deadly consequences. A 2014 study even suggested that the public sees hurricanes with traditionally male names as more dangerous — leading them to take more precautions — which has led hurricanes with female names to kill more people overall.

However, the study has been widely criticized due to a major flaw: Hurricanes only started receiving male names in 1979, but the 2014 study used 60 years’ of hurricane damages, skewing the data. (In fact, if you remove Hurricane Sandy from the dataset, male hurricanes turn out to be deadlier overall.)

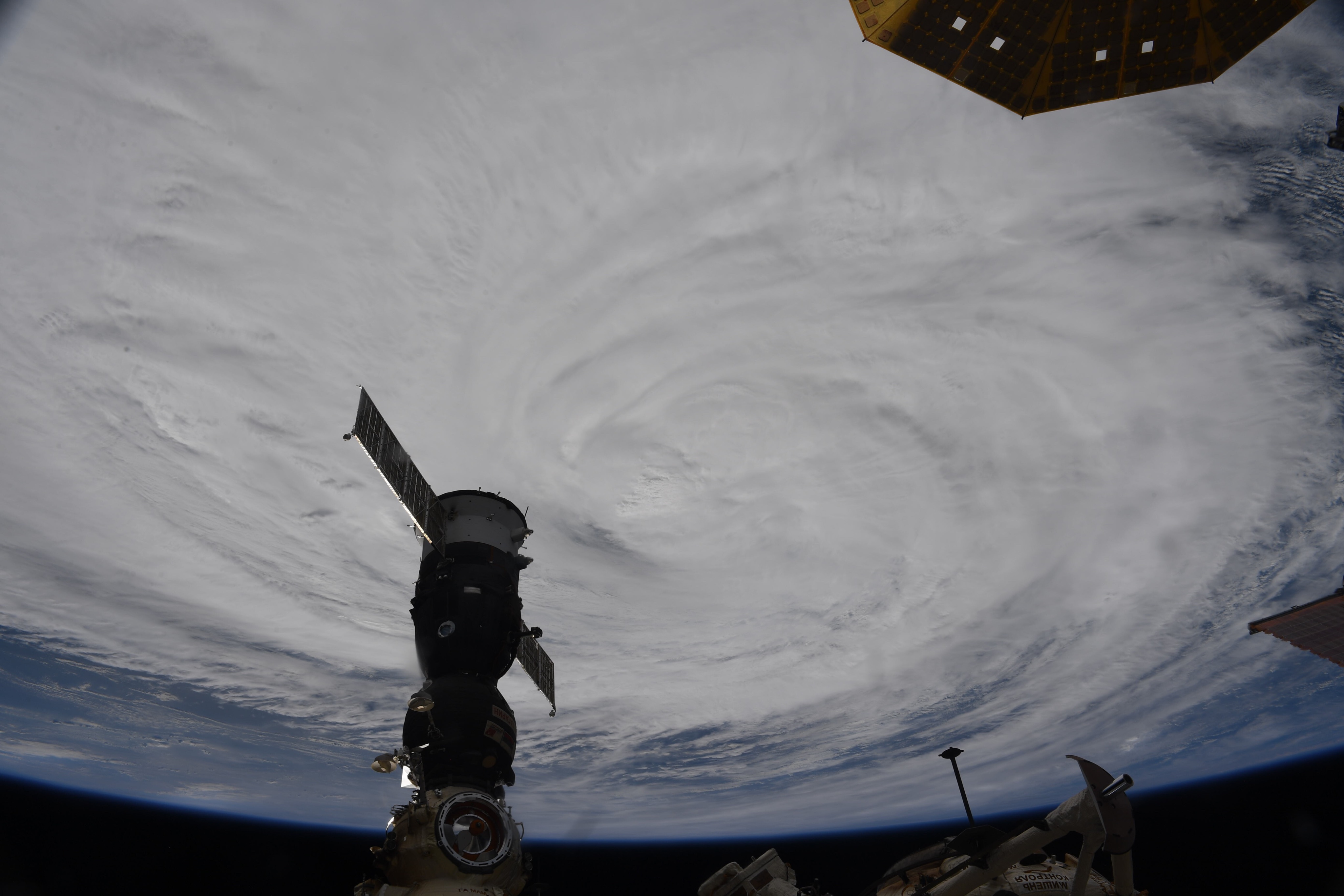

What’s more, hurricanes have gotten far less deadly over the years, largely thanks to the satellites that allow us to predict the path of hurricanes.

“It’s been a great and unsung success story,” Emanuel said. “Before the satellite era, you could have storms out in the open ocean that no one ever saw or measured. They just went undetected. We’ve gotten better at making deductions at storm deductions of storm intensity, though we’re still not that good at it.”