At 7 kelvin — a temperature so cold that even air would freeze solid — a single molecule sits on a copper surface. It is, by most reckoning, one of the smallest objects ever deliberately interrogated: a ring of four carbon atoms and one nitrogen, with hydrogen atoms bristling from its edges. A tungsten tip hovers nanometres above it, measuring the quantum trickle of electrons. Then the laser pulses.

The molecule flips.

Not randomly, not thermally, but in direct response to a beam of infrared light tuned to resonate with the precise frequency at which its nitrogen-hydrogen bond stretches. The tip records the switch. The switch is the spectrum. And for the first time, a single molecule has sung its own vibrational fingerprint, one note at a time, to a patient listener that can hear it.

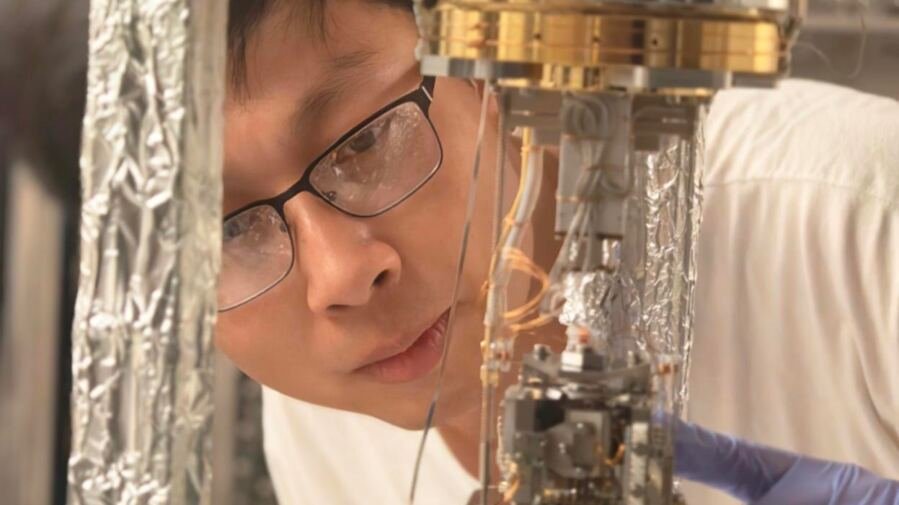

The technique, developed by Shaowei Li and colleagues at UC San Diego and published this week in Science, marries two powerful but previously incompatible tools. Infrared spectroscopy has been chemistry’s workhorse for well over a century: shine light of the right frequency at a molecule, watch it absorb, and you learn which bonds are present. The trouble is resolution. Infrared light has wavelengths measured in micrometres, and the diffraction limit means you can never focus it tightly enough to pick out a single molecule from the crowd. Scanning tunnelling microscopy, by contrast, can image individual atoms with ångström precision. But its sensitivity to vibrations has always been restricted by the narrow energy windows that electron tunnelling can probe.

Li’s group combined infrared excitation with tunnelling current detection, calling the resulting platform IRiSTM. The idea is disarmingly simple in principle: if you tune your laser to a frequency that excites a particular molecular vibration, and that vibration causes the molecule to move — even slightly — the tunnelling current will change. But making it work required eliminating a host of confounding signals, particularly the thermal expansion of the tip itself, which the researchers suppressed with an active piezoelectric feedback scheme.

To validate the approach they started small. The ethynyl radical, just two carbon atoms and one hydrogen, was deposited onto copper and illuminated across a broad infrared range. At 3,169 wavenumbers, corresponding to the carbon-hydrogen stretch, the molecule began rotating rapidly between its four equivalent orientations on the surface. Tune away from that frequency and the rotation slows. Replace the hydrogen with a heavier deuterium atom and every peak shifts predictably to lower energy, as basic physics requires. The isotope substitution did what it always does in spectroscopy: it confirmed the assignment beyond doubt.

Having established the method, the team turned to something biologically weightier. Pyrrolidine — the five-membered ring at the heart of the amino acid proline — is one of the most consequential small molecules in structural biology. The “proline kink” it generates disrupts the regular geometry of proteins, forcing bends and twists that shape enzyme active sites, membrane receptors, and the triple helix of collagen. Pyrrolidine’s ring is not rigid: it flexes between two conformations, axial and equatorial, a motion chemists call ring puckering. At the temperatures relevant to biology, that puckering happens spontaneously and constantly. At 6.3 kelvin on a copper surface, it needs a push.

The laser provides the push. Scanning across nearly the full mid-infrared range, the team measured how different vibrational excitations altered the rate of switching between the two conformers. The resulting spectrum was strikingly richer than anything conventional techniques had revealed. As well as the fundamental nitrogen-hydrogen and carbon-hydrogen stretches, the spectrum showed overtones — the molecular equivalent of harmonics — at twice and three times the fundamental frequencies, and combination bands where two different vibrational modes pooled their energy. Some of these features, particularly a cluster between 4,500 and 5,500 wavenumbers attributed to modes coupling into the ring-puckering motion, were entirely invisible to standard infrared methods.

That invisibility is meaningful. IRiSTM follows different selection rules from conventional spectroscopy, because the signal depends not just on whether a vibration absorbs infrared light, but on whether it translates into measurable nuclear motion. The carbon-hydrogen stretch, clearly visible in bulk infrared measurements, was absent from the IRiSTM spectrum of pyrrolidine: it absorbs light readily enough, but the resulting energy dissipates rapidly into other channels without pushing the ring toward its conformational switch. The ring-deformation overtones do the opposite: their large nuclear displacements couple directly into the puckering coordinate, making them stand out clearly despite being weak absorbers in ensemble measurements.

The team confirmed this picture by swapping hydrogens for deuteriums in controlled ways — replacing only the nitrogen-hydrogen, or replacing all eight carbon-hydrogens, or both. Each isotopologue produced a distinctive spectrum, and crucially, each could be identified microscopically. When the laser was tuned to the nitrogen-deuterium stretch, only the N-deuterated pyrrolidine molecules flickered; their neighbours sat still. Tune to the carbon-deuterium stretch and a different subset lit up. The technique could, in principle, identify which variety of an otherwise visually identical molecule sits at any given surface site — a capability with obvious relevance for studying catalysts, where the chemical identity of individual adsorbed species can determine whether a reaction proceeds at all.

“Infrared spectroscopy is one of our most powerful tools, but until now it has always been an ensemble technique,” said Li. “This gives us a way to see, at the most fundamental level, how vibrational energy couples to molecular motion.”

That coupling question has frustrated chemists for decades. The dream of bond-selective chemistry — of tuning a laser to a specific vibration and steering a reaction down a chosen pathway — has foundered repeatedly on the reality that vibrational energy dissipates almost instantly into neighbouring modes before it can do useful work. Understanding exactly which vibrations couple to which motions, and how quickly, is a prerequisite for making bond-selective control practical. IRiSTM provides a direct experimental window into precisely those dynamics, one molecule at a time, in an environment where the local surroundings can be controlled and varied systematically.

The copper surface and near-absolute-zero temperatures are experimental necessities for now. But the underlying principle — using conformational switching or some other molecular motion as a transducer for infrared absorption — is not obviously limited to cryogenic conditions. Whether the technique can eventually migrate to room-temperature environments, or to molecules of sufficient complexity to be directly biologically relevant, remains to be seen. For the moment, a five-atom ring flexing on a cold copper plate is enough. After a century of listening to molecular choirs, chemistry has finally heard a solo.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Thank you for standing with us!