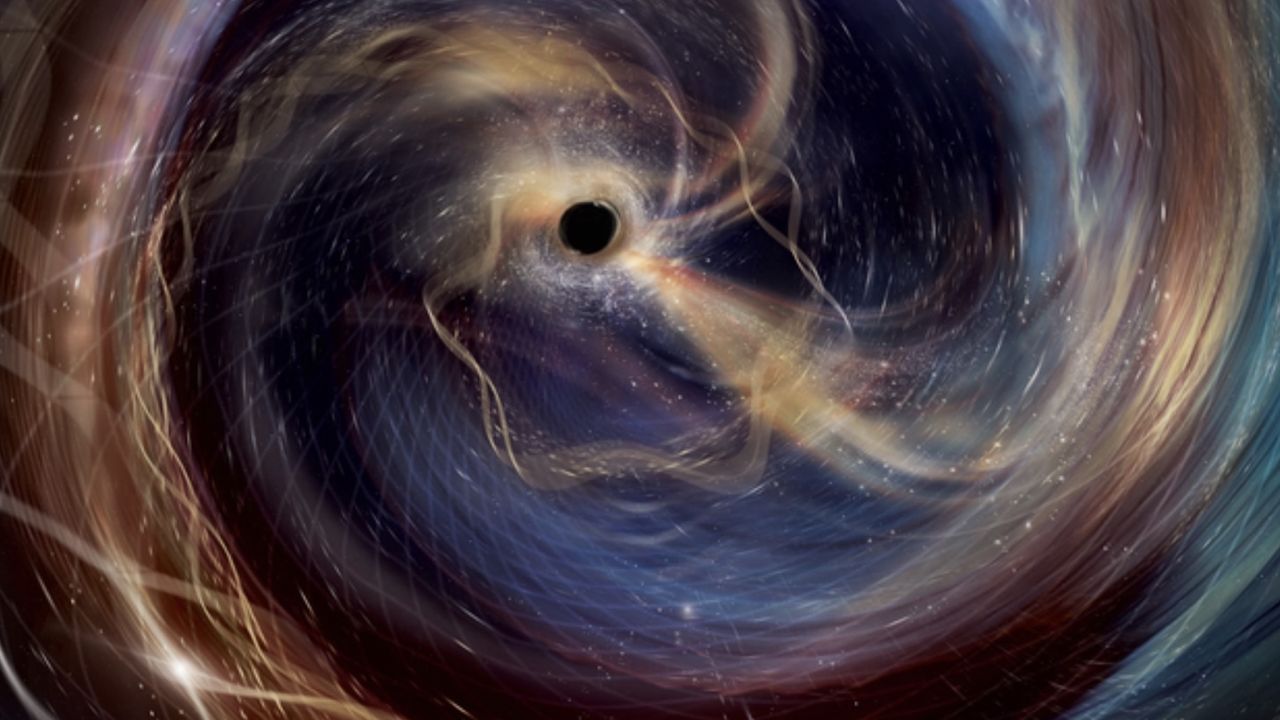

Scientists have found two pairs of merging black holes, and they think the larger one in each merger is a rare “second-generation” veteran of a previous collision.

The two larger black holes’ unusual behavior, observed through ripples in space-time called gravitational waves, was described Oct. 28 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The results “provide tantalizing evidence that these black holes were formed from previous black hole mergers,” study co-author Stephen Fairhurst, a professor at Cardiff University in the U.K. and a spokesperson for the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, said in a statement.

Back-to-back mergers

The research was based on two recently detected mergers that occurred just a month apart. Analyzing the gravitational wave signatures from these events allowed the researchers to infer the mass, rotation and distances of the black holes involved.

In the first event, on Oct. 11, 2024, scientists spotted two black holes — measuring six and 20 times the mass of the sun, respectively — colliding in a merger known as GW241011, roughly 700 million light-years from Earth. The larger black hole was one of the fastest-rotating black holes ever found.

The second merger, GW241110, was found on Nov. 10, 2024, with black holes that were eight and 17 times the mass of the sun. This merger was farther away, at 2.4 billion light-years. The larger black hole was also spinning opposite to its orbit, which has never been seen before.

Scientists say each of these mergers had novel properties, including that the bigger black hole in each merger was nearly double the size of the smaller one, and that the larger black holes were spinning oddly compared with the hundreds of other mergers observed through gravitational waves since the historic first detection by LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) in 2015.

The scientists suggested that the larger black hole in each merger previously coalesced in a process called a “hierarchical merger,” which would happen in dense environments like star clusters, where black holes would frequently come near each other.

“This is one of our most exciting discoveries so far,” study co-author Jess McIver, an astrophysicist at the University of British Columbia, said in the statement. “These events provide strong evidence that there are very dense, busy pockets of the universe driving some dead stars together.”

Aside from the possible second-generation black hole finds, scientists said that the two mergers validated physics laws predicted by Albert Einstein more than a century ago and that the events are helping scientists learn more about elementary particles.

For example, GW241011 generated a clear signal that allowed scientists to see the larger black hole deforming as it spun, due to the black hole’s rapid rotation. The resulting signature in the gravitational waves matched up with theories from Einstein, as well as from mathematician Roy Kerr, concerning rotating black holes.

That same event also generated a “hum” in the gravitational-wave signal, created because the larger black hole was much larger than the smaller one. (The hum is similar to musical instrument overtones, the collaborators stated.) This observation also helped confirm predictions from Einstein.