Table of Contents

NOAA and NASA report that the 2025 ozone hole over Antarctica was far smaller and shorter-lived than usual. Falling chlorine levels and a weaker polar vortex helped limit ozone loss this season.

These findings add to decades of evidence showing that the Montreal Protocol is working. Scientists expect the ozone layer to keep strengthening in the coming decades.

2025 Antarctic Ozone Hole Ranks Among Smallest in Decades

Scientists at NOAA and NASA report that this year’s Antarctic ozone hole is the fifth smallest measured since 1992 — the same year the Montreal Protocol began reducing the use of ozone-depleting chemicals.

During the peak of the 2025 ozone depletion season, which lasted from September 7 through October 13, the ozone hole covered an average of about 7.23 million square miles (18.71 million square kilometers). It has also begun to break apart almost three weeks earlier than the typical timing seen over the past ten years.

“As predicted, we’re seeing ozone holes trending smaller in area than they were in the early 2000s,” said Paul Newman, a senior scientist at the University of Maryland system and longtime leader of NASA’s ozone research team. “They’re forming later in the season and breaking up earlier.”

Peak Measurements and Long-Term Comparisons

The largest single-day size for the 2025 hole occurred on September 9, when it expanded to 8.83 million square miles (22.86 million square kilometers). That is roughly 30% smaller than the biggest ozone hole ever recorded, which occurred in 2006 and averaged 10.27 million square miles (26.60 million square kilometers).

NASA and NOAA have also tracked the size of the ozone hole using records that go back to 1979, when satellite measurements began. Within that 46-year period, the 2025 ozone hole ranks as the 14th smallest.

Montreal Protocol Continues To Drive Ozone Recovery

According to NOAA and NASA researchers, this year’s observations reinforce the clear impact of the Montreal Protocol and its later amendments, which have sharply reduced emissions of ozone-depleting chemicals. Scientists say the ozone layer remains on track to return to pre-ozone hole conditions later this century as nations continue to adopt less harmful alternatives.

“Since peaking around the year 2000, levels of ozone depleting substances in the Antarctic stratosphere have declined by about a third relative to pre-ozone-hole levels,” said Stephen Montzka, senior scientist with NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory.

“This year’s hole would have been more than one million square miles larger if there was still as much chlorine in the stratosphere as there was 25 years ago,” added NASA’s Newman.

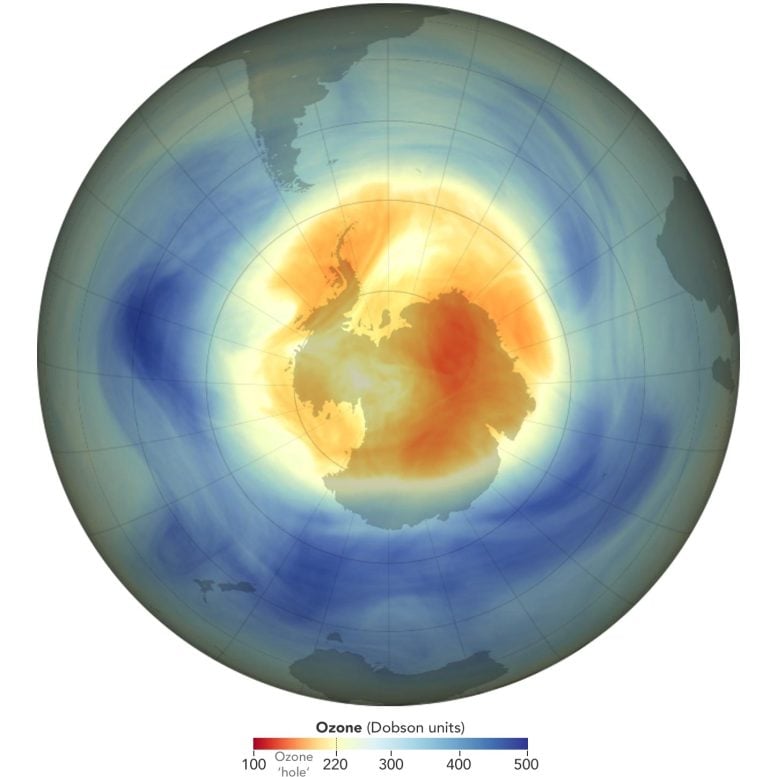

Weather balloon measurements showed that in 2025 the ozone layer directly above the South Pole dropped to a minimum value of 147 Dobson Units on October 6. The lowest measurement ever recorded in this region was 92 Dobson Units in October 2006.

How Ozone Protects the Planet

Earth’s ozone layer functions as a protective shield that limits the amount of ultraviolet (UV) radiation reaching the surface. It lies within the stratosphere, which extends from about 7 to 31 miles above the ground. When ozone concentrations fall, more UV radiation can penetrate to the surface, contributing to crop losses, higher rates of skin cancer and cataracts, and other health and environmental concerns.

Ozone depletion occurs when chlorine- and bromine-containing compounds drift into the stratosphere. There, intense UV sunlight breaks them apart, releasing reactive chlorine and bromine that destroy ozone molecules. For many years, Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and other ozone-depleting compounds were widely used in products such as aerosol sprays, foams, air conditioners, and refrigerators. The chlorine and bromine they contain can linger in the atmosphere for decades. American leadership in science, technology, and policy has been central to identifying these risks and encouraging actions that preserve both the ozone layer and public health.

Legacy Emissions and Long-Term Ozone Recovery

Although these chemicals are now banned, they remain locked inside older materials such as building insulation or stored in landfills. As emissions from these legacy sources continue to decline, researchers expect the Antarctic ozone hole to recover (get smaller) by the late 2060s.

Laura Ciasto, a meteorologist with NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center and a member of the ozone research team, explained that natural variations also shape year-to-year ozone behavior. Temperature patterns, weather systems and the strength of the polar vortex — a band of strong winds surrounding Antarctica — all influence the size of the ozone hole.

“A weaker-than-normal polar vortex this past August helped keep temperatures above average and likely contributed to a smaller ozone hole,” said Ciasto.

Global Monitoring From Space and the Ground

Tracking the ozone layer requires coordinated global measurements. Scientists use instruments aboard NASA’s Aura satellite, the NOAA-20 and NOAA-21 satellites, and the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership satellite operated jointly by NASA and NOAA.

NOAA teams also gather data from weather balloons and upward-looking surface-based instruments that measure stratospheric ozone directly above the South Pole Atmospheric Baseline Observatory.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.