I was reading a piece in The Times last month which hailed the flannel trouser as the new trend in menswear. It’s funny how the mainstream can sometimes take a long time to catch up – it must be 15 years since the growth of ‘classic menswear’ led to guys embracing flannel as the perfect smart/casual material, halfway between suits and chinos. Or maybe the trend is just going round again.

Of course, many of the brands featured in that article were also ruining the flannel trouser, with elasticated waists and too-light materials. But in the grand scheme of things it’s probably good – it’s all education. Apparently Paul Smith and Corneliani think suits are back too.

It did remind me – more importantly – of a question readers ask about flannel trousers, which is how robust they are: how strong and long-lasting. Every week or two there’s a comment from someone who’s busted through the crotch of theirs, and wants to know if there’s anything they can do about it.

Flannel is not the strongest material in the world. It’s certainly not as strong a denim or most chinos. It’s often not as strong as suit trousers either – the fact they’re worsted rather than woollen helps, although they will often go shiny before they wear through, which is not a great look either.

But if cared for properly, flannel trousers should be a great servant in your wardrobe, able to be worn for many years. So let’s look at the different issues in turn, beginning with what we mean by ‘cared for properly’.

Care and wear

This is basic stuff really, that applies to most tailoring. But it’s particularly relevant if you’re trying to find ways to protect soft materials.

- Rotation. All wool trousers benefit from not being worn every day. Wool is much weaker when it is damp, and your perspiration can take more than a night to dry out. Wear them every other day at the most.

- After care. Look after your flannels. Hang them up when you take them off in the evening, give them a press every now and again. Don’t leave them scrumpled in the corner. It will keep them looking good and steam helps clean them too. An occasional brush down is also good.

- Dry clean as little as possible. An extension of this brushing and steaming point is that it should allow you to dry clean the trousers as little as possible, as that will prematurely age the fabric.

- Activity. Smart trousers are not meant for cycling in. Some heavier, tougher materials can be used for that (they were used for riding back in the day, after all) but flannels usually can’t be. If you wear them for active pursuits, it will shorten their life.

Fabric and fit

The flannels you actually buy, in terms of fabric and cut and how they fit, will make just as big a difference as how they are worn. All these points will also stop flannels bagging out or losing shape.

- Denser fabric. Flannels that are woven more densely, unsurprisingly, will be stronger. In general, English flannels are woven in this way whereas Italian ones are softer and not as dense.

- Heavier fabric. To an extent, heavier weights are also better. However, there is a point where heavy fabrics create more friction and can even wear out faster. You see this with some heavy denims. So 13-15oz is better than 9-10oz in flannels, but don’t push much heavier.

- Looser fit. I remember one reader asking about flannels wearing fast, but admitted they were tight on the thighs and he wore them cycling. Tight fits put materials under more pressure (though as with all these things, you don’t want super loose either).

Alternatives

If you follow this advice and your flannel trousers still don’t last very long, you might need to look at alternative materials. In general, what you sacrifice is the fuzzy texture (‘nap’), which is thing that makes them more casual. But there’s a sliding scale. It runs something like this:

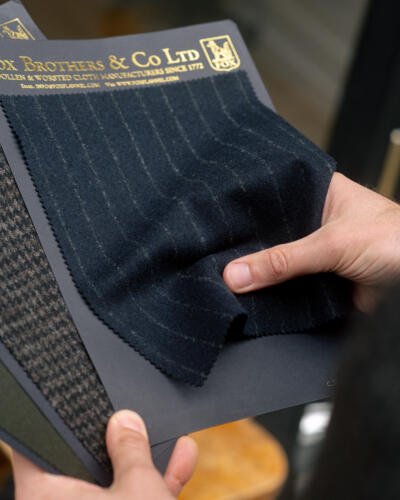

- Worsted flannel. The first step is going for a flannel that uses worsted yarn rather than woollen. Often worsted yarn is used for lighter weights, but it doesn’t have to be. I like Fox’s 12/13oz worsted flannel but there is a small sacrifice in terms of the texture.

- Shooting tweeds. Tweeds made for shooting are dense and hardy, and often smoother than normal tweed. Something like Thornproof can be a flannel substitute, in shades of grey, but it is rough and heavy.

- Heavy high-twists. High-twist materials naturally have more texture – different to flannel, but still a texture that separates them from regular suit trousers. The issue is they’re mostly for spring/summer as they’re so breathable, and people mostly wear flannels for autumn/winter. Still, in a heavier weight or warmer location they can be a good option. The best greys for me are in the Spring Ram bunch.

- Whipcords. Materials like whipcord, cavalry twill and covert are among the toughest out there and not as heavy as the shooting tweeds. They are smoother though, and sometimes have a bit of a sheen, taking them further away from flannel. Something like this from Holland & Sherry for instance.

- Heavy worsteds. If the nap of flannel really isn’t a priority, suit trousers that are heavier and slightly coarser will have more more texture than ones that are lighter and finer. We covered this in detail here, and among those I’d recommend the Universal bunch.

Repairs

If all else fails and your flannels need repairing, this is possible, though they’ll never be quite the same. The key is to:

- Catch it early. Repairs are a lot easier when the material is thinning but not actually holed through. That way similar flannel can be placed on the inside of the trousers, rather than the outside, making the repair less visible.

- Use an experienced alterations tailor. If there is a hole, a piece of flannel can be stitched on the outside and on a hidden area like the crotch, it won’t necessarily be that noticeable. But use a good tailor – ones we recommend in London here and New York here.

- Even reinforce in advance. If you know wearing is going to be a problem, or the trousers are precious, patches like this can even be done on the inside in anticipation of future issues. The material will always be a little thicker and perhaps not quite as comfortable though.

A lot of these points have been mentioned over the years in different posts, but it’s good to gather them together.

I should re-emphasise that most of them apply to all tailoring as well – patching might be harder on lighter or patterned materials, and you won’t want double thickness on heavier cloths, but the care points should all be kept in mind.

And to finish, here’s some close-ups of the flannel alternatives.