Table of Contents

Astronomers thought they’d found an exoplanet. For years, a bright dot called Fomalhaut b orbited a nearby star, reflecting starlight through clouds of dust. Then it disappeared. When Hubble looked again in 2023, a different bright spot had materialized elsewhere in the same debris belt, 23.4 astronomical units away from where the first one had been.

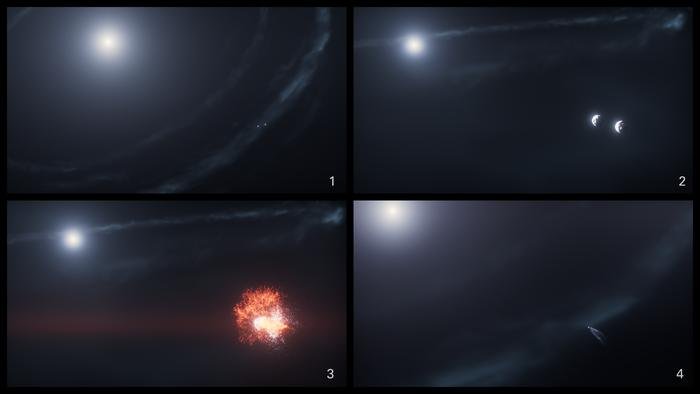

The revelation was immediate: these weren’t planets at all. They were the glowing wreckage of planetesimals (rocky bodies tens of kilometers across) that had collided at speeds high enough to vaporize rock into fine dust. The star Fomalhaut, just 25 light-years from Earth, had become the site of two documented cosmic smashups in 20 years. It’s the first time anyone has watched this process unfold twice in the same system beyond our solar neighborhood.

Jason Wang, an astrophysicist at Northwestern University, was part of the team monitoring Fomalhaut when the second collision became visible. The system’s massive dust belt (one of the largest known) made it an easy target for long-term study, but nobody expected to catch lightning striking twice. The original source, now called cs1, had appeared in 2004 near the belt’s inner edge at roughly 120 astronomical units from the star. By 2013 it was accelerating outward, pushed by radiation pressure on its smallest dust grains. A year later, it had faded below detection limits.

“Spotting a new light source in the dust belt around a star was surprising. We did not expect that at all,” Wang explains. “Our primary hypothesis is that we saw two collisions of planetesimals over the last two decades.”

Dust Clouds Posing as Worlds

The second source, cs2, sits at 135.3 astronomical units in 2023 observations and appears 30% brighter than cs1 was at its peak in 2012. Four independent analysis methods confirmed it wasn’t a background object or pre-existing feature. Follow-up imaging in 2024 caught a candidate source displaced northward by about 110 milliarcseconds, suggesting it’s already moving on a highly eccentric orbit with an estimated eccentricity around 0.8.

To generate the observed brightness, each collision likely involved bodies roughly 30 kilometers in radius (small by planetary standards but massive enough to release dust clouds with total cross-sectional areas around 5 × 10²² square centimeters). Most of that mass comes from grains just a few microns across, the size that reflects visible light efficiently before radiation pressure ejects them from the system entirely. Over the 440 million years since Fomalhaut formed, these cs1-scale events have probably occurred 22 million times, stripping away about 0.04 Earth masses from the debris belt.

The spatial proximity of cs1 and cs2 (separated by just 8.1 degrees along the belt) raises questions about whether the collisions are random. Theory predicts one such event every 100,000 years or longer; seeing two in two decades suggests either extraordinary luck or some dynamical mechanism concentrating impacts. Infrared observations have revealed a misaligned intermediate dust belt at 94 astronomical units with higher eccentricity, but its orbital plane intersects the outer belt about 70 degrees away from where both collisions occurred. Mean-motion resonances with an unseen planet could cluster planetesimals in the cs1/cs2 region, though millimeter-wave observations haven’t detected the expected over-density.

What This Means for Planet Hunting

The discovery carries practical consequences for exoplanet searches. Dust clouds from fresh collisions can mimic the appearance of planets reflecting starlight for a decade or more before dispersing. As next-generation instruments like the Giant Magellan Telescope begin hunting for habitable-zone worlds around nearby stars, distinguishing transient debris from genuine planets will require years of careful monitoring, or risk announcing discoveries that fade away.

The research team has secured time on the James Webb Space Telescope to observe Fomalhaut in near-infrared wavelengths, where color data can reveal dust grain sizes and composition. Whether the colliding bodies were dry and rocky or contained water ice matters for understanding what materials eventually coalesce into planets. Hubble’s aging spectrograph can no longer collect reliable data from the system, but Webb’s instruments should track cs2’s evolution and potentially catch details about the parent planetesimals’ internal structure.

Fomalhaut keeps rewriting its own story. What began as excitement over a possible exoplanet has become a front-row seat to the violent, messy process of world-building, complete with the reminder that even 440 million years after formation, planetary systems remain dynamically active enough to surprise us.

Related

Discover more from European Space Agency Tracker

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.