Will There Be a White Christmas This Year? It Depends on Where You Live

Are you dreaming of a white Christmas? The odds of snow on the big day comes down to a mix of climate and weather, scientists explain

A view of the Christmas tree at Rockefeller Center as snow falls on December 21, 2024, in New York City.

Craig T Fruchtman/Getty Images

Dreaming of a white Christmas or not, the chances of actually seeing snow on December 25 come down to both the prevailing climate wherever you live and the weather leading up to and on the day.

For some of us in the U.S., it’s a lock; for others, the odds are sadly slim. And in many places, they are getting slimmer as global temperatures rise and winter weather gets wetter. As atmospheric scientist Colin Zarzycki of Pennsylvania State University puts it, “If stuff’s going to fall out of the sky on December 24, if it’s warmer, it’s more likely to fall as rain.”

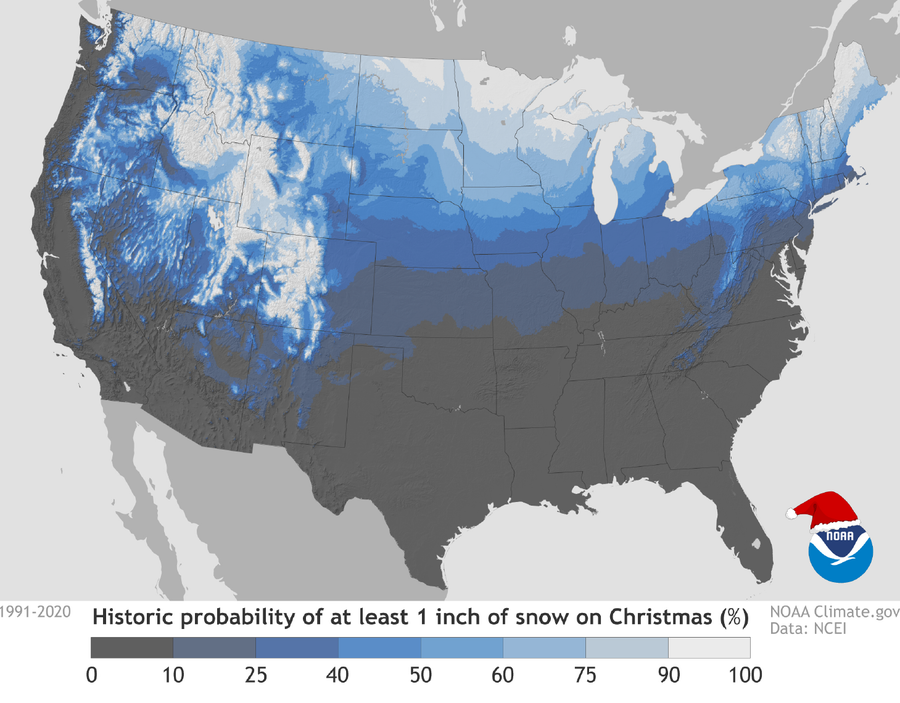

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Source: National Centers for Environmental Information (data)

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Some places in the U.S. where one can be fairly certain to see at least an inch of snow on the ground on Christmas Day are about what you’d expect—the higher elevations in the Rocky Mountains, for example, and the northernmost stretches of the upper Midwest and the Northeast, according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric data from 1991–2020. Beyond these regions, a broad swath of Utah, Nebraska, Wisconsin and the Northeast has roughly 50–50 odds of snow on the ground when Santa comes to town. For anyone in Kansas, Kentucky, Virginia and anywhere else in the South, don’t hold your breath.

For winter precipitation to fall as snow, the air needs to be at or below freezing. As the planet warms, the places that will be cold enough for snow will be limited to the most northern locations and highest elevations. The start and end of winter will likely become too warm for snowflakes in many places, too—“you narrow in the window where you can actually have snow,” Zarzycki says.

Broadly, the first day of snow is falling later than it used to across the U.S., and the odds of a white Christmas are shrinking. For some places in, say, southern Ohio, this could mean a 15 percent chance of snow shrinking to 5 percent, whereas, for northern Vermont, an 85 percent chance might become a 75 percent chance.

There are local oddities, however, particularly in places that see lake-effect snow from the Great Lakes. Lake-effect snow happens when bitter winter winds blow over the relatively warm lake waters, pulling up moisture that then falls as snow on nearby shores. Warming means the lakes are taking longer to ice over, so for a time, those areas could actually see more snow overall and greater snowfall later into the winter than they did in the past.

Similarly, when nor’easters or other big storms that can dump loads of snow move through, they could lead to more snow than in the past—at least for a time. Imagine a world where the winter temperature is 25 degrees Fahrenheit (minus four degrees Celsius) instead of 20 degrees F (minus seven degrees C), as in the past, Zarzycki says. The higher temperature is still cold enough for snow, but the warmer atmosphere can also hold more moisture, so “you actually get a more intense snowstorm.” Observations seem to bear out this trend in southern Canada and the northern U.S.

In other words, in a given area, there might be, say, 40 percent fewer days when it is cold enough to snow, but the average amount of snowfall in a season may only drop by 20 percent. If winter temperatures warm too far, however, storms are just going to bring rain.

As for this year, current forecasts aren’t in favor of a snowy Christmas for most of the country. A winter heat dome is predicted to make temperatures higher than normal across most of the contiguous U.S., with the Great Plains and the South, as National Weather Service put it on X, “trading the Snowman for a Sunburn!”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.