Table of Contents

Tiny grains of dust from asteroid Bennu are reshaping how scientists think life’s ingredients formed in space.

Scientists previously identified amino acids, the essential components of life, inside 4.6-billion-year-old rocks collected from the asteroid Bennu. These samples were brought back to Earth in 2023 by NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission. While the discovery confirmed that life’s basic ingredients exist beyond Earth, how those molecules formed in space remained unclear. New research led by scientists at Penn State now suggests these amino acids may have emerged in extremely cold, radiation-rich conditions during the earliest days of the solar system.

The findings, published today (February 9) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, indicate that several amino acids found in Bennu did not form through the processes scientists had long assumed. Instead, they appear to have developed under harsh environmental conditions unlike those previously associated with amino acid formation.

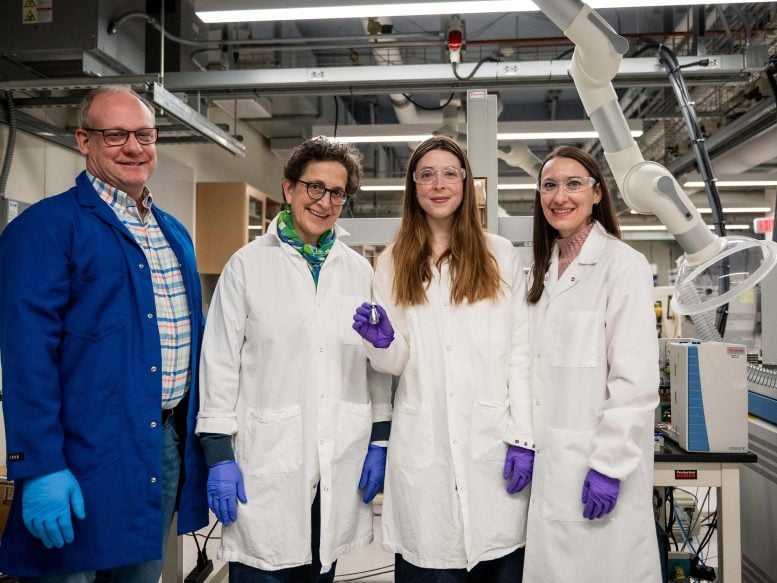

“Our results flip the script on how we have typically thought amino acids formed in asteroids,” said Allison Baczynski, assistant research professor of geosciences at Penn State and co-lead author on the paper. “It now looks like there are many conditions where these building blocks of life can form, not just when there’s warm liquid water. Our analysis showed that there’s much more diversity in the pathways and conditions in which these amino acids can be formed.”

Studying Bennu’s Dust at the Atomic Level

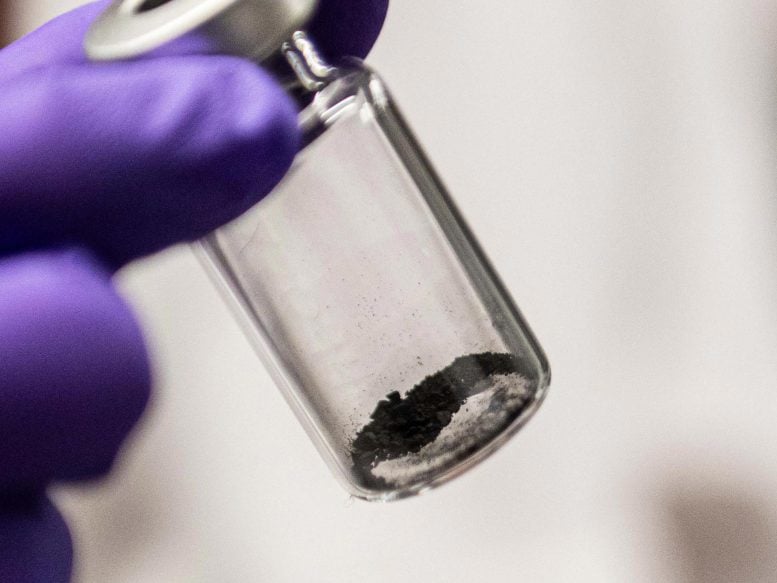

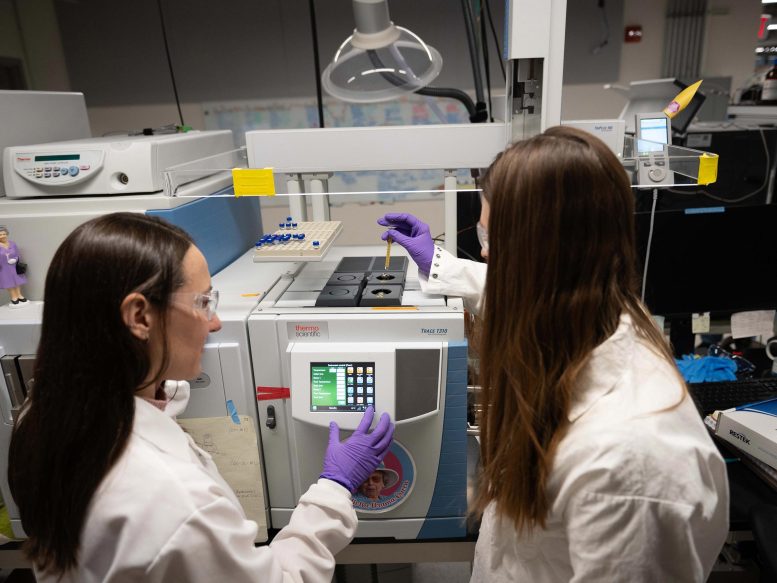

To uncover these details, researchers examined a tiny amount of asteroid material, roughly the size of a teaspoon. Using specialized instruments designed to detect isotopes, or subtle differences in atomic mass, the team closely analyzed the chemistry of the samples. Their work focused on glycine, the simplest known amino acid and one of the most basic molecular ingredients required for life.

Amino acids connect to form proteins, which are responsible for nearly all biological functions, from building cells to driving chemical reactions. Glycine’s simple structure makes it especially useful for tracing early chemical processes that occurred before life began.

Baczynski explained that glycine can form under many different chemical scenarios and is often used as a marker of early prebiotic chemistry. When glycine is found in asteroids or comets, it strengthens the idea that some of life’s foundational molecules may have formed in space and later reached Earth.

Rethinking How Amino Acids Formed in Space

For many years, scientists believed glycine formed primarily through a process known as Strecker synthesis. In this scenario, hydrogen cyanide, ammonia, and aldehydes or ketones react in liquid water. However, the Bennu samples tell a different story. The isotopic signatures suggest that glycine on Bennu may have formed without liquid water, instead developing in frozen ice exposed to radiation in the outer regions of the early solar system.

“Here at Penn State, we have modified instrumentation that allows us to make isotopic measurements on really low abundances of organic compounds like glycine,” Baczynski said. “Without advances in technology and investment in specialized instrumentation, we would have never made this discovery.”

Comparing Bennu to the Famous Murchison Meteorite

Scientists have long relied on carbon-rich meteorites to study amino acids from space. One of the most well-known examples is the Murchison meteorite, which fell in Australia in 1969. The Penn State team compared the amino acids found in Bennu with those previously analyzed from Murchison.

The comparison revealed a striking contrast. Amino acids in the Murchison meteorite appear to have formed in environments that included liquid water and relatively mild temperatures. These conditions could have existed on the meteorite’s parent body and were also present on early Earth.

“One of the reasons why amino acids are so important is because we think that they played a big role in how life started on Earth,” said Ophélie McIntosh, postdoctoral researcher in Penn State’s Department of Geosciences and co-lead author on the paper. “What’s a real surprise is that the amino acids in Bennu show a much different isotopic pattern than those in Murchison, and these results suggest that Bennu and Murchison’s parent bodies likely originated in chemically distinct regions of the solar system.”

New Mysteries About Life’s Chemical Beginnings

The findings raise new questions that researchers are now eager to explore. Amino acids exist in two mirror-image forms, similar to left and right hands. Scientists previously assumed that these paired forms would share identical isotopic characteristics. In the Bennu samples, however, the two mirror-image forms of glutamic acid show dramatically different nitrogen values.

Why these chemically identical but mirrored molecules carry such different isotopic signatures remains unknown. Solving that puzzle could reveal even more about how life’s building blocks formed across the solar system.

“We have more questions now than answers,” Baczynski said. “We hope that we can continue to analyze a range of different meteorites to look at their amino acids. We want to know if they continue to look like Murchison and Bennu, or maybe there is even more diversity in the conditions and pathways that can create the building blocks of life.”

Reference: “Multiple formation pathways for amino acids in the early Solar System based on carbon and nitrogen isotopes in asteroid Bennu samples” 9 February 2026, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2517723123

Other Penn State co-authors are Mila Matney, doctoral candidate in geosciences; Christopher House, professor of geosciences; and Katherine Freeman, Evan Pugh University Professor of Geosciences at Penn State.

Other authors on the paper are Danielle Simkus and Hannah McLain of the Center for Research and Exploration in Space Science and Technology (CRESST) at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland; Jason P. Dworkin, Daniel P. Glavin and Jamie E. Elsila of NASA Goddard’s Solar System Exploration Division; and Harold C. Connolly Jr. of Rowan University, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona, and Dante S. Lauretta of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona.

The research was funded by multiple NASA programs, including the New Frontiers Program, which funded the OSIRIS‑REx mission, and several NASA research awards, along with support through NASA’s CRESST II partnership.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.