By using controlled microwave noise, researchers created a quantum refrigerator capable of operating as a cooler, heat engine, or amplifier. This approach offers a new way to manage heat directly inside quantum circuits.

Quantum technology has the potential to reshape many core areas of society, including drug discovery, artificial intelligence, logistics, and secure communications. Despite this promise, major engineering hurdles still stand in the way of practical applications. One of the most serious challenges is maintaining control over quantum states, which are extremely sensitive and form the foundation of quantum computing.

Superconducting quantum computers push this challenge to an extreme. To work at all, they must be cooled to temperatures near absolute zero (around -273°C). In that deep cold, electrical resistance vanishes, electrons flow freely, and qubits can reliably form the quantum states that carry information. The catch is that the same qubits can lose that information quickly if they feel tiny temperature changes, unwanted electromagnetic signals, or everyday background noise.

Scaling Challenges and the Problem of Heat

Quantum computers need many more qubits to solve real problems, but larger devices are harder to keep quiet and evenly cold. As circuits grow, heat and noise have more ways to spread, which increases the risk of wiping out quantum information.

“Many quantum devices are ultimately limited by how energy is transported and dissipated. Understanding these pathways and being able to measure them allows us to design quantum devices in which heat flows are predictable, controllable, and even useful,” says Simon Sundelin, doctoral student of quantum technology at Chalmers University of Technology and the study’s lead author.

Using noise for cooling

In a study published in Nature Communications, the Chalmers team reports a “minimal” quantum refrigerator that flips the usual strategy. Instead of spending all effort on suppressing noise, they use a controlled version of it to drive heat transport predictably.

“Physicists have long speculated about a phenomenon called Brownian refrigeration, the idea that random thermal fluctuations could be harnessed to produce a cooling effect. Our work represents the closest realization of this concept to date,” says Simone Gasparinetti, associate professor at Chalmers and senior author of the study.

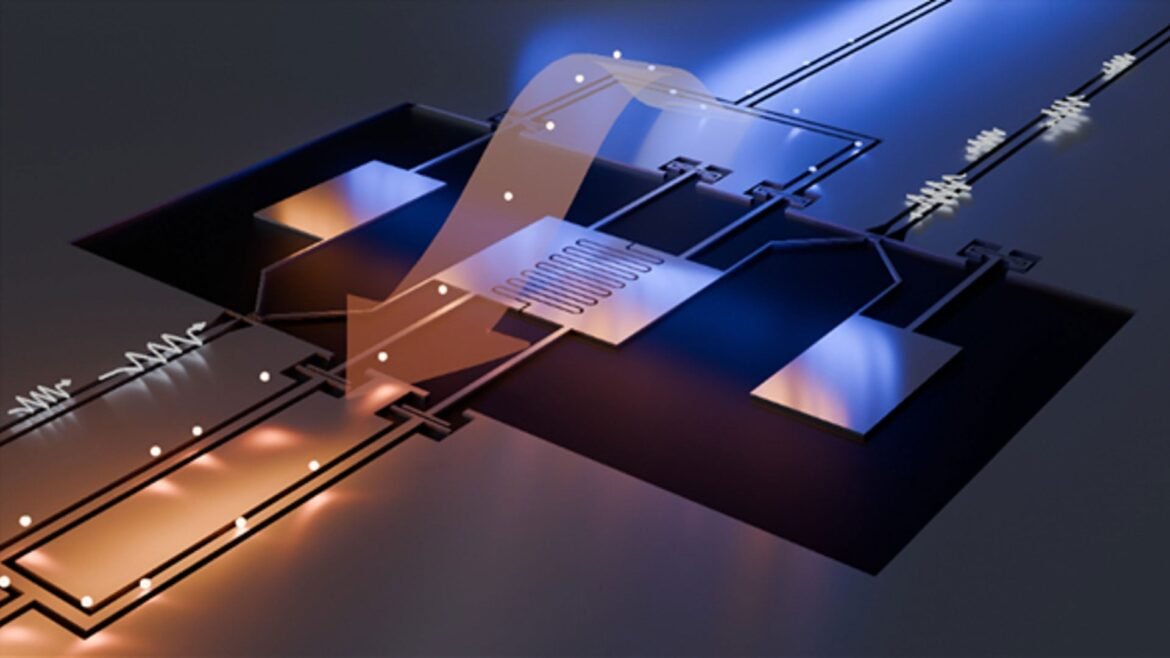

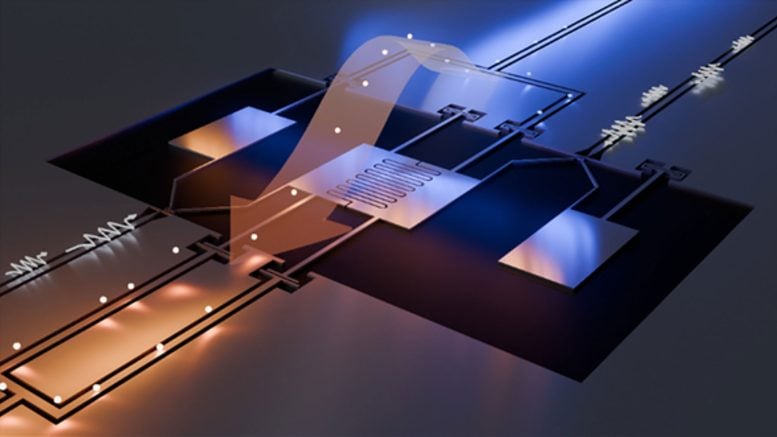

The core of the device is a superconducting artificial molecule created in Chalmers’ nanofabrication laboratory. While it mimics the behavior of natural molecules, it is built from tiny superconducting circuits rather than atoms. By linking this artificial molecule to multiple microwave channels and adding controlled microwave noise as random fluctuations within a narrow frequency range, the researchers can guide how heat and energy move through the system with high precision.

Precision Heat Control at the Smallest Scales

“The two microwave channels serve as hot and cold reservoirs, but the key point is that they are only effectively connected when we inject controlled noise through a third port. This injected noise enables and drives heat transport between the reservoirs via the artificial molecule. We were able to measure extremely small heat currents, down to powers in the order of attowatts, or 10⁻¹⁸ watt. If such a small heat flow were used to warm a drop of water, it would take the age of the universe to see its temperature rise one degree Celsius,” explains Sundelin.

Because they can tune reservoir temperatures and track these tiny heat flows, the same setup can switch between operating modes, acting as a refrigerator, a heat engine, or a thermal transport amplifier. That flexibility is important for large quantum processors, where the hottest spots are often created right where qubits are controlled and measured, not at the edges of the cryostat.

“We see this as an important step towards controlling heat directly inside quantum circuits, at a scale that conventional cooling systems can’t reach. Being able to remove or redirect heat at this tiny scale opens the door to more reliable and robust quantum technologies,” says Aamir Ali, a researcher in quantum technology at Chalmers and co-author of the study.

Reference: “Quantum refrigeration powered by noise in a superconducting circuit” by Simon Sundelin, Mohammed Ali Aamir, Vyom Manish Kulkarni, Claudia Castillo-Moreno and Simone Gasparinetti, 26 January 2026, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-67751-z

Funding: The research project has received funding from: the Swedish Research Council; the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation through the Wallenberg Centre for Quantum Technology (WACQT); the European Research Council; and the European Union.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.