Table of Contents

There was a time when Haji Ghulam Rasool Khan’s hands told stories — of tradition, colour, and Kashmiri heritage — through the delicate swirls of Jamawar patchwork. But in 1998, a cruel twist of fate brought that to a halt.

A devastating accident in New Delhi left him bedridden and silent, his world narrowed to a single room in Srinagar. Yet from that stillness emerged something unexpected: a return to the very art that had once defined his childhood, now reborn with deeper meaning.

Confined to a room and cut off from the rhythm of everyday life, Khan could have let grief consume him. But instead, from that quiet space of stillness and pain, he reached back into the folds of his childhood — to a craft once learned, then forgotten.

Rediscovering forgotten craft

From within those four walls, Khan tirelessly honed his craft, transforming the traditional Jamawar patchwork art to a global stage, captivating customers worldwide with its intricate beauty.

“Every success comes at the cost of sacrifice, and for me, it was my leg,” says Khan, smiling warmly. “In 1989, I met with a motorcycle accident in Delhi. The doctors told me my leg would not recover. But I did recover, and during that period, I also learned the forgotten Jamawar patchwork art.”

700 Years, 700 craftsmen: The roots of a Kashmiri art that refuses to fade

The centuries-old Jamawar art of Kashmir, which dates back to the 14th century, endures as a vibrant emblem of the region’s cultural legacy and artisanal excellence.

Shaped by Persian artistic influences and elevated under the patronage of the Mughal emperors, Jamawar shawls are distinguished by their intricate paisley and floral motifs, rendered with remarkable precision on fine pashmina or silk. At the heart of this tradition is the painstaking Kani weaving technique—an exacting process involving the use of tiny wooden bobbins to craft elaborate, tapestry-like patterns.

Many, including Khan, trace the origins of Jamawar patchwork to the 14th century, when the revered Sufi saint Mir Syed Ali Hamadani (R.A.) journeyed from Iran to Kashmir. It is said he arrived with 700 master craftsmen, who made Amda Kadal in downtown Srinagar their home, quietly planting the seeds of an art form that would be cherished for centuries.

Where the past lives in thread and cloth

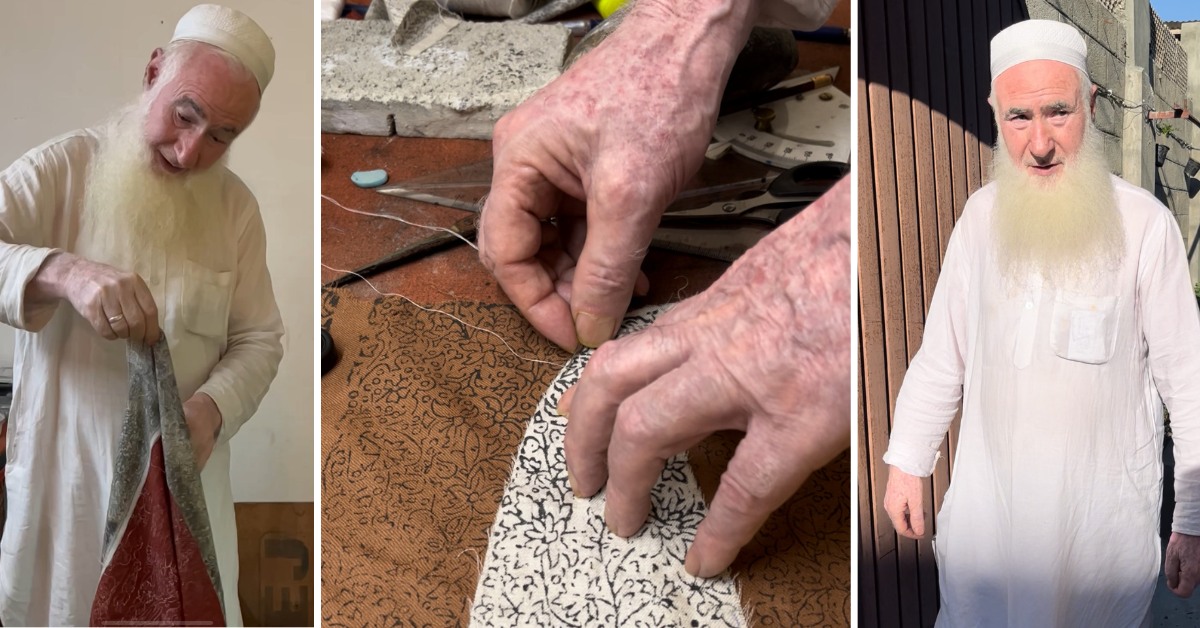

In a quiet bylane of Amda Kadal, one of Srinagar’s oldest neighbourhoods, 70-year-old Haji Ghulam Rasool Khan sits on the floor of his modest workshop. Light filters in through a small window, falling gently on the grey shawl stretched across his lap. Around him are neat piles of fabric, containers of dyed thread, and the faint scent of pashmina.

This is where he spends most of his day — not just working, but remembering, rebuilding, and creating.

Khan still personally dyes the fabric for his patchwork shawls. Each one is distinct. There are no repeats, no printed patterns. His hands move with the kind of familiarity that comes from decades of living closely with the material, not just as an artisan, but as someone who turned to this work in solitude and stayed with it through devotion.

Decades of work, and the world noticed

What began in a single room has reached homes across the country and beyond. Khan’s patchwork pieces — known for their detail, balance, and complexity — have earned him wide recognition. He speaks of it lightly, but his wall carries the weight of it all: the State Award in 2003, the National Award in 2005, the Shilp Guru Award in 2010, the Padma Shri in 2021, and the Pradhan Mantri Vishwakarma Award in 2023.

Each certificate, framed and slightly faded, is a quiet marker of how far he has come — from a room he couldn’t leave to being celebrated across the country.

“The ideas come to me… I don’t plan them”

On the day we visit, Khan is dressed in a white kameez and shalwar, sitting cross-legged on the floor, stitching the outline of a peacock onto a light grey shawl. He doesn’t use a sketchbook or a stencil. The ideas, he says, come unannounced.

“Divinely inspired, I weave intricate sketches of peacocks, almonds, ducks, eagles, forests, and lakes into our shawls. These beautifully embroidered designs and patchwork creations are cherished worldwide, with demand soaring for their exquisite craftsmanship,” he says, without pausing his work.

He doesn’t boast — he explains, not as someone trying to impress, but as someone trying to stay faithful to something larger than himself.

“Every success comes at the cost of sacrifice; for me, it was my leg.”

There’s no bitterness in his voice—just a kind of calm clarity — like someone who’s made peace with both pain and purpose.

‘Woven with patience and skill’: Preserving a dying tradition

In Srinagar’s Bemina locality, Nazir Ahmad Parray, a long-time observer of Kashmir’s art and craft scene, recalls a time when Jamawar shawls were more than fashion — they were a source of identity, a link to heritage.

“Jamawar was always popular, woven with patience and skill. But with the arrival of machines, the art began to fade as cheaper shawls took over the market,” he says. “Still, artisans like Khan have kept the craft alive, and thanks to their dedication, people from far and wide continue to seek their work.”

Parray is speaking to a more profound shift that many in the valley have witnessed over the past few decades. As mass-produced shawls flooded the market in the 1990s, authentic Jamawar, which requires weeks, even months of meticulous handwork, struggled to compete on price and visibility. Yet, a handful of artisans, including Haji Ghulam Rasool Khan, continued to work the old way, thread by thread.

Khan is known for his patchwork pieces and his mastery of traditional Sozni and Kani embroidery techniques — both of which demand intense labour, precision, and years of experience to perfect. His reputation has grown well beyond Kashmir. As the Chairman of the J&K Art & Craft Development Society, he has become one of the leading voices for artisan welfare in the region.

Over the years, Khan has participated in international exhibitions and emporia, taking Kashmir’s craft traditions to global platforms. His displays are often among the most admired — not just for their visual intricacy, but for the history they carry in every motif.

Heritage in demand

According to Khan, Jamawar Pashmina shawls are primarily sold in India, but they also find buyers in countries such as Brazil, South Korea, and across the Middle East. “Every year, thousands of tourists from around the world visit Kashmir to experience its breathtaking landscapes, and during their stay, many also purchase the region’s famous handicraft items, especially shawls celebrated for their intricate paisley and floral motifs, meticulously woven or hand-embroidered on fine pashmina or silk,” says Khan, as he carefully embroiders patterns on a tray shawl.

Such is the demand for his work that Khan does not believe in the market. “There is a huge demand for our items, but due to the shortage of skilled artisans, not many orders are accepted. We do not need the market, the market needs us because our patchwork Pashmina shawls are deeply appreciated and valued by our customers, who are willing to pay a good amount for them. For example, a fine Pashmina shawl with Jamawar patchwork is sold for Rs. 15,000, making my job beyond imagination,” he explains, while dedicating himself to conserving the oldest form of Kashmiri shawl technique.

Determined to ensure its longevity, he is breathing new life into a forgotten art form and is actively working to pass it down to the next generation, envisioning a legacy that will thrive for centuries to come.

“I want to take this art forward, but the government should establish a dedicated training centre where aspiring artisans and young students can learn the craft with ease. The work is demanding, and a single shawl can take months or even years to complete. It takes three months to start work on a shawl from scratch until completion. The work demands a lot of patience, which is why people are fleeing from this art and refusing to learn it. It stands as a testament to the patience and skill that define this timeless Kashmiri tradition.”

Preserving art amid challenges

Khan, with his grey flowing beard, adds that handicraft demands patience, a quality often lacking in the younger generation. “I once worked on a project, a 64-piece shawl, which took over five years to complete with the help of my apprentices. If I did not have patience, I would not have reintroduced the forgotten art of Jamawar shawl-making.”

The septuagenarian claims that, to this day, there is not a single artisan in the Valley who can create Jamawar patchwork on shawls as he does. “No one can do Jamawar work like I do. Though I have trained many people in the past, including my brother, they lack the accuracy and dedication required for this craft. I would be over the moon to see artisans stepping into my shoes, and they would also get all the awards I receive.”

For Khan, another reason Jamawar work has struggled to progress is the declining respect for handicrafts in Kashmir. A growing craze for white-collar jobs has led many to look down on traditional artisan work.

However, Director of Handicrafts and Handloom Kashmir, Mussarat Islam, tells The Better India that 432 centres across Kashmir are currently functioning under the department, where various traditional art forms, including Khan’s Jamawar patchwork, are officially recognised and taught.

“At each centre, skilled artisans, including 4 to 5 master craftsmen like Khan are training budding artists who also receive stipends and allowances,” he said. “To further promote Jamawar patchwork, we are actively introducing it under various government schemes aimed at preserving and expanding this heritage craft.”

At Khan’s workshop, it’s not unusual to find young men and women sitting beside him, observing, asking questions, learning slowly — stitch by stitch. Some come from families of artisans, others are drawn by curiosity. What they all share is the desire to keep something alive — not just a technique, but a way of seeing the world.

In a time when traditional crafts are often reduced to souvenirs, Khan’s story — and the quiet work being done across Kashmir — reminds us that these art forms still have life, meaning, and a future in the hands of people who care.

Edited by Leila Badyari