Table of Contents

Picture a cap studded with electrodes, bristling like some strange technological creature. It looks intimidating, sure, but what researchers in Italy and Switzerland have discovered is rather beautiful. It might just restore movement to limbs that should be frozen forever.

When a spinal cord is severely damaged, the wiring goes down. But here’s the thing: the limbs still work perfectly well. The brain hasn’t forgotten its job either. The communication line between them is simply severed. A person trying to move a paralyzed leg sends the signal out from their motor cortex. The message travels down the spine, hits the break in the cord, and stops dead. It’s like calling someone on a phone that’s been cut in half.

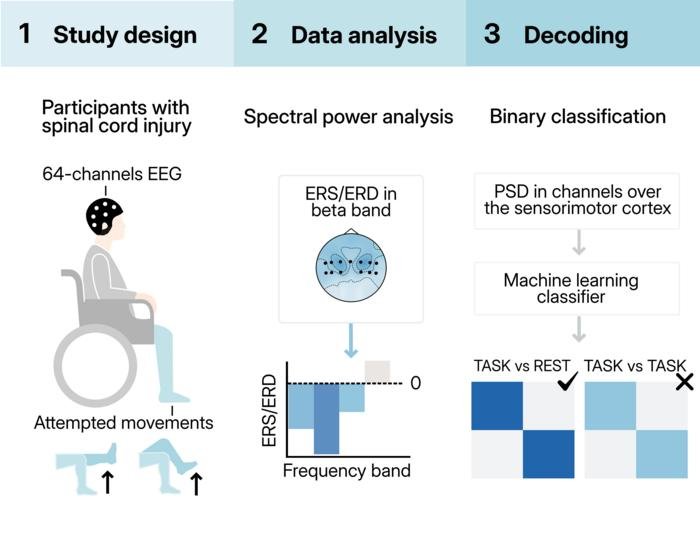

So researchers asked a question that seems obvious once you hear it: what if we intercepted that signal before it hits the broken part? What if we caught it at the source, read what the brain is trying to say, and fed that instruction somewhere more useful? Specifically, we could feed it to an implant that stimulates the spinal cord below the injury. This creates a bridge around the damage. It’s called a brain-spine interface, and now there’s evidence it might work without opening someone’s skull.

Non-Invasive vs. Invasive Approaches

Most brain-spine interface research has relied on invasive approaches. Surgeons implant electrodes directly into the brain or on its surface. These capture signals with precision from deep within the tissue. The problem is obvious: brain surgery carries risks, infections, and complications.

There’s a simpler alternative hiding in plain sight. Electroencephalography, or EEG, sits on top of the scalp. It captures brain activity through a cap of sensors.

“It can cause infections; it’s another surgical procedure,” explains Laura Toni, who led the research at Italian and Swiss universities. The researchers wondered whether they could avoid invasive approaches altogether. For paralyzed people already managing life-changing injuries, avoiding another surgical intervention isn’t trivial.

The Challenge of Signal Depth

But EEG has a big limitation. The deeper the brain activity you’re trying to read, the harder it becomes. The scalp and tissues muffle the signal, much like listening to someone through several walls. This matters because lower-limb control happens in the brain’s central regions, buried beneath layers of tissue. That’s different from reading hand and arm movements, which are processed on the brain’s outer surface.

“The brain controls lower limb movements mainly in the central area, while upper limb movements are more on the outside,” Toni says. “It’s easier to have a spatial mapping of what you’re trying to decode compared to the lower limbs.”

The team decided to test whether this anatomical challenge could actually be overcome. Four patients with severe spinal cord injuries participated, each with varying degrees of paralysis. The patients attempted four movements repeatedly across multiple sessions:

- Flexing the hip (left and right)

- Extending the knee (left and right)

Promising Results and Future Directions

What emerged was a tentative “yes,” but with caveats worth considering carefully. The EEG signals could reliably tell the difference between attempts to move and periods of rest. That worked reasonably well, particularly in patients whose injuries were less complete.

The harder part was specificity. Can you tell left leg movements from right? Hip movements from knee movements? That remained frustratingly hard in most cases, though machine learning helped somewhat when combining multiple predictions.

The researchers didn’t expect perfection. What they got was something arguably more valuable: proof that the fundamental barrier isn’t impossible to cross. The signals are weak, but they are there. About one second of attempted movement provides enough information for reliable detection. That window matters because it suggests a simplified control system might actually work. This could trigger a preset movement sequence rather than requiring continuous, moment-to-moment control.

None of this happens in isolation from lived reality. The patients were undergoing rehabilitation during the study. Some received spinal cord stimulation therapy. All dealt with the mundane challenges of chronic paralysis and pain. Performance varied across sessions, reflecting fatigue, attention, and motivation. These factors all affect how strongly the brain signals broadcast themselves. In some ways, that’s a limitation of the study. In others, it’s evidence the approach might actually work in clinical settings.

Where does this lead? The researchers are already thinking ahead:

- Improving algorithms to distinguish between different movement attempts

- Refining the process to work better in real-world conditions

- Scaling up to larger patient groups

The gap between what’s possible in the lab and what’s practical in daily life remains real. But somewhere beneath all that technical complexity is a simple human fact: a person’s brain still knows how to walk. It still remembers the signal for standing, for stepping forward. All we needed was a way to listen. The cap of electrodes might just be that listener.

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!