Do you know why deductions are more valuable than tax credits? Here’s a rundown of basic tax issues to understand

Reviews and recommendations are unbiased and products are independently selected. Postmedia may earn an affiliate commission from purchases made through links on this page.

Article content

If you don’t prepare your own tax return each year, you’re missing out on what’s possibly the best education you can get about our Canadian tax system. Each week during tax season, I get dozens of emails from readers asking a variety of questions. Many are excellent and require a bit of research for me to properly respond. Others, however, show that some Canadians don’t really have a good understanding of how our tax system works.

Advertisement 2

Article content

Article content

Article content

Truthfully, though, they can’t be blamed. Our personal tax system, with its myriad deductions, credits, calculations, claw-backs, limitations and endless complexities is not for the faint of heart. But it’s important to have a basic understanding of why deductions are typically more valuable than tax credits, or why choosing to defer claiming a registered retirement saving plan (RRSP) contribution to a later year can make sense.

This week, let’s go back to basics and take a closer look at how the Canadian personal tax system, with its progressive tax brackets, deductions and credits, works.

Let’s begin with our tax brackets. Individuals pay taxes at graduated rates, meaning that your rate of tax gets progressively higher as your taxable income increases. The 2025 federal brackets are: zero to $57,375 of income (15 per cent); above $57,375 to $114,750 (20.5 per cent); above $114,750 to $177,882 (26 per cent); above $177,882 to $253,414 (29 per cent), with anything above that taxed at 33 per cent. Each province also has its own set of provincial tax brackets and rates.

Article content

Advertisement 3

Article content

While graduated tax rates are applied to taxable income, not all income is included and certain amounts may be deducted, thereby reducing the base to which marginal tax rates are applied. For example, capital gains are only partially taxed. Unlike ordinary income, such as employment income or interest income that is fully included in taxable income, only 50 per cent of capital gains are included in income, so the tax rate is lower than for ordinary income.

For example, let’s say you realized capital gains of $10,000 from the sale of publicly-traded shares in 2024, and had no other capital gains or losses last year. Only 50 per cent of this amount, or $5,000, would be taxed. If instead you earned interest or net rental income of $10,000, you would pay tax on the entire amount.

Common deductions that you may subtract from your total income, thereby decreasing your taxable income, include: RRSP and first home savings account (FHSA) contributions, moving expenses, childcare expenses, interest expense paid for the purpose of earning income, investment counselling fees for non-registered accounts, and many more.

Advertisement 4

Article content

Once you calculate the tax payable on your taxable income at the progressive rates above, you then calculate and deduct the various non-refundable tax credits to which you may be entitled. In contrast to deductions, tax credits directly reduce the tax you pay after marginal tax rates have been applied to your taxable income. With tax credits, a fixed rate is applied to eligible amounts and the resultant credit amount offsets taxes payable.

Common non-refundable credits include: the basic personal amount, the spousal amount, the age amount, medical expenses, tuition paid and charitable donations, among numerous others. Nearly all non-refundable credits are multiplied by the federal non-refundable credit rate of 15 per cent, which corresponds to the lowest federal tax bracket. Corresponding provincial or territorial non-refundable credits may also be available, but the amounts and rates vary by province or territory.

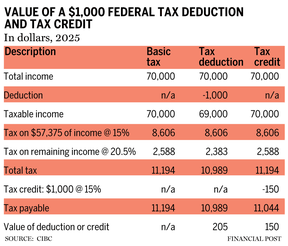

With this background, let’s look at an example that shows how a tax deduction yields tax savings at the marginal tax rate that varies with your income level, while a tax credit yields tax savings at a fixed rate. Suppose you have a total income of $70,000 and claim either a $1,000 deduction (for, say, an RRSP contribution) or claim a federal non-refundable credit for $1,000 (for, say, eligible medical expenses beyond the minimum threshold).

Advertisement 5

Article content

The amount of the deduction is subtracted from income, so that this amount of income is not taxed. In column three in the accompanying chart, a $1,000 tax deduction yields $205 of federal tax savings, calculated as the $1,000 deduction multiplied by the marginal tax rate that would have applied to the income (20.5 per cent). Consequently, a deduction yields federal tax savings at your marginal tax rate.

On the other hand, the $1,000 of eligible medical expenses generates a federal non-refundable credit of 15 per cent, yielding a federal tax savings of only $150. When you add provincial or territorial tax savings to the federal savings above, the total tax savings can range from about 20 per cent for the combined credits to more than 50 per cent for a deduction, depending on your province or territory of residence.

Recommended from Editorial

-

CRA demands arrears interest on donation tax shelter

-

CRA can collect tax debt from spouses under circumstances

-

CRA’s ‘stupid mistake’ compels taxpayer to pay extra taxes

The accompanying chart illustrates that unless you’re in the lowest 15 per cent federal tax bracket (income below $57,535), tax deductions are generally more valuable than tax credits. There are some exceptions, such as for donations above $200 annually, political contributions, and the eligible educator school supply tax credit, where the federal credits are worth more than 15 per cent.

Advertisement 6

Article content

Finally, as the chart shows, since a tax deduction saves tax at your marginal rate, postponing a deduction (where permissible, such as an RRSP or FHSA contribution) to a later year when you’ll be in a higher marginal tax bracket, means that it may be worth more as its value would be based on your higher marginal rate in that future year.

Jamie Golombek, FCPA, FCA, CFP, CLU, TEP, is the managing director, Tax & Estate Planning with CIBC Private Wealth in Toronto. Jamie.Golombek@cibc.com.

If you liked this story, sign up for more in the FP Investor newsletter.

Bookmark our website and support our journalism: Don’t miss the business news you need to know — add financialpost.com to your bookmarks and sign up for our newsletters here.

Article content