Life’s building blocks may not have been crafted in the lightning flashes of a tempest, a new study suggests, so much as in the ceaseless glow of rolling ocean mists.

Researchers from Stanford University have demonstrated a phenomenon they call ‘microlightning’ is able to generate organic compounds necessary for life, putting a far gentler spin on the long-disputed Miller-Urey model of biogenesis.

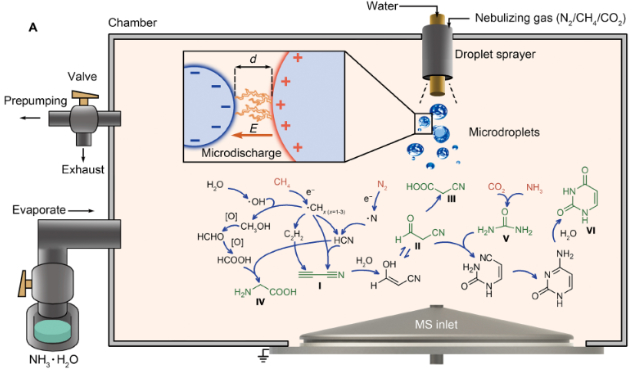

Their experiments show that a spray of charged water droplets can exchange electrons in tiny sparks of light, and sufficiently ionize gas in the surrounding air to encourage carbon and nitrogen to bond into larger compounds.

Though the findings fall short of explaining how a mix of basic molecules merged into the first replicating cells, they pose yet another possible path for the synthesis of compounds that form the basis of proteins and DNA.

“Microelectric discharges between oppositely charged water microdroplets make all the organic molecules observed previously in the Miller-Urey experiment,” says senior author and chemist Richard Zare.

“We propose that this is a new mechanism for the prebiotic synthesis of molecules that constitute the building blocks of life.”

In 1952, the American chemist Stanley Miller conducted a series of now-famous experiments under the supervision of the Nobel laureate Harold Urey.

Cycling a mix of heated water and simple gases such as methane and ammonia through laboratory apparatus, Miller demonstrated it was possible to create a variety of amino acids by applying a spark of electricity.

Though the relevance of the experiment’s results to Earth’s ancient conditions has been heavily debated, the Miller-Urey study was a landmark in the quest to describe how simple elements that include carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen can come together in complex ways without the guidance of existing life forms.

Lightning could feasibly provide the energy required for these chemical reactions, but our planet’s oceans are vast and deep. To transform them into a soup of organic acids bubbling with potential, the sky would need to crackle with electrical activity for eons.

Inspired by recent experiments that found the voltage between water microdroplets could fix nitrogen into nitrogen oxides, Zare and his colleagues conducted their own, to discover the true power within a cloud of vapor.

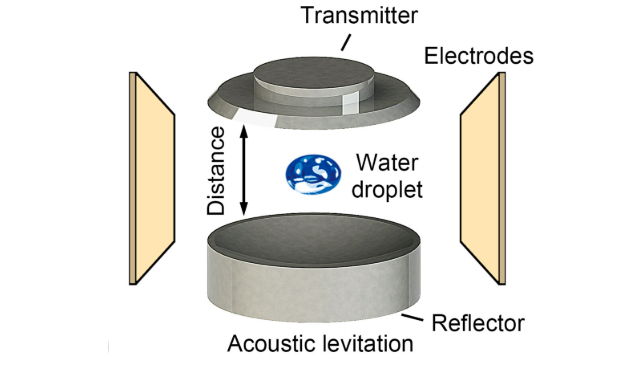

Their high-speed imaging of sound-levitated water droplets revealed the emission of photons whenever electrons jumped between masses of different sizes and charges. The researchers referred to this effect as microlightning.

As tiny as these flashes were, they hinted at an impressive amount of energy concentrated in a tiny space.

Spraying a mist into a gas mixture of nitrogen, methane, ammonia, and carbon dioxide, the researchers observed the formation of larger molecules that include the nucleic acids uracil, amino acid glycine, and hydrogen cyanide – a precursor to a soup of other organic building blocks.

This doesn’t rule out a myriad of other possible avenues for life’s chemical precursors to form, whether from lightning, the shock of meteorite impacts, or delivered on the backs of comets.

If anything, it could point to an inevitability of biochemistry throughout the Universe. Wherever water is whipped into a mist in the right gases, we might expect life has a chance to assemble.

“On early Earth, there were water sprays all over the place – into crevices or against rocks, and they can accumulate and create this chemical reaction,” says Zare.

“I think this overcomes many of the problems people have with the Miller-Urey hypothesis.”

This research was published in Science Advances.