What artists wear, as projection and performance

by Philipp Fröhlich.

The artist is one of the most enduring archetypes of personal style – romanticised, quoted, and frequently featured in the fashion world. Part of this appeal lies in the cultural cachet artists carry: collaborations such as Yayoi Kusama with Louis Vuitton lend collections a visual identity that carries both artistic weight and an aura of exclusivity.

But it’s also because artists often dress in striking, evocative ways. Even when not consciously styled, their appearance can carry a performative dimension. Whether deliberate or instinctive, it becomes part of the image they construct, a way of shaping how their work and persona are perceived.

Artists’ clothing choices often reflect a careful negotiation between necessity, self- expression, and self-projection.

Before considering how they dress for the world, it makes sense to begin where most of the artist’s time is spent: the studio. As a space of privacy and production, the studio permits near-total freedom in dress. Functionality is usually reduced to its essentials: whatever keeps you warm in winter, cool in summer, and allows for ease of movement.

Clothes inevitably become stained with paint or materials, and many artists wear garments long retired from public use. A few adopt overalls for convenience, but most reach for whatever old clothes are at hand, not unlike what one might wear for gardening.

Studio clothing follows its own logic, shaped more by habit and necessity than by aesthetics. Yet even in this utilitarian context, clothing can carry symbolic weight.

Just as one might rely on music, light, or routine to signal the start of a creative process, what one wears can help establish a sense of purpose or focus. Some artists dress with intention for work, not out of vanity, but to enter the studio with a certain attitude or resolve.

At the other end of the spectrum are public appearances, with exhibition openings being the most visible.

As in many areas of life, formality at these events has declined dramatically, often replaced by a general uncertainty about what is appropriate. You might see artists dressed in anything from a tailored suit to worn jeans and an untucked shirt. But for better or worse, each of them has likely considered how they want to appear at their own opening.

The shift from the privacy of the studio to the visibility of public events makes these appearances particularly charged. The outfit may not be carefully calibrated, but it is rarely thoughtless. Sometimes, choosing a low-key look is itself a deliberate stance, an effort to sidestep as many clichés as possible about what an artist should look like.

Then there is a third, and perhaps most revealing, category: the in-between situation of a studio visit.

For the visitor, entering an artist’s studio is a rare privilege, an invitation into the inner sanctum of their world. It holds a status not unlike that of a mage’s tower, a space charged with privacy, mystery, and control.

And when someone steps into that space, the artist must decide how to appear. If their work clothes are presentable, they are usually the first choice. After all, standing in a studio without paint-stained clothing can feel as unnatural as entering a lab without a lab coat. In these visits, what the artist wears becomes a performance of authenticity, whether it is deliberately curated or casually worn.

Most studio photographs fall into this category. They are not candid glimpses into the working process but carefully shaped portrayals. When a photographer visits, no artist simply continues painting without thought. Each gesture, outfit, and composition is considered.

The photographs of Francis Bacon, shot by Michael Holtz, for instance, show him within the theatrical chaos of his studio, a scene so intense it borders on constructed mise-en-scène. These images echo his paintings, where isolated figures are staged inside stark, cage-like forms. His posture is often sensitive, almost shy, elegant and introspective amid the raw disarray.

In contrast, Jackson Pollock presents a different image entirely. In Hans Namuth’s iconic photographs, Pollock appears as pure action and instinct, almost a cowboy with a brush. Dressed in paint-splattered jeans and T-shirt, he embodies the all-American, working-class painter. The photos, full of smoke and motion, could have passed for a mid-century cigarette ad. It is an image so compelling that it became inseparable from the myth of Pollock himself.

These varying contexts create a persistent tension for artists, who often carry a deep awareness that the way they present themselves will inevitably shape how their work is perceived.

While many artists have developed memorable styles, a select few have come to embody the archetype so vividly that their image circulates far beyond the art world. These figures are often reduced to a single trait and used as reference points in fashion, each representing a distinct stylistic facet of the artist myth.

Often portrayed as the quintessential bohemian in Breton stripes, shorts, Grecian slippers, or a beret, Pablo Picasso’s image has been endlessly recycled, from Saint Laurent campaigns to Uniqlo graphic T-shirts.

Yet the abundance of photographs suggests a more calculated relationship to appearance. He posed for the camera bare-chested and with theatrical confidence, sometimes donning costumes or wigs, and frequently consulted his tailor Sapone for outfits designed to impress.

Beneath the bohemian persona lay a fiercely competitive instinct. His clothing choices were as much about commanding attention as they were about expressing creativity.

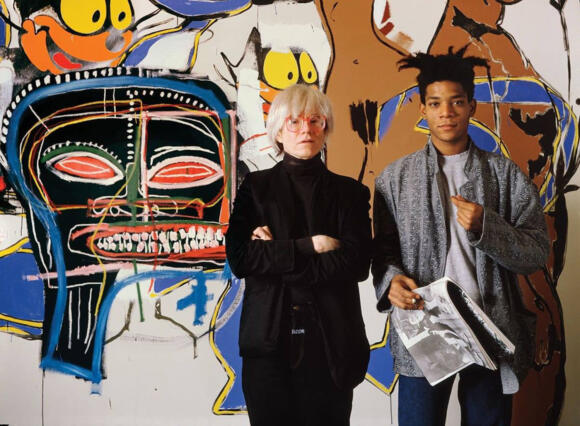

Basquiat’s style was an ingenious combination of designer pieces such as Comme des Garçons, Armani, or Issey Miyake with worn thrift-shop clothing and a carefully unkempt appearance.

This layered approach mirrored the tensions in his work, blending high culture with raw immediacy. He often painted in the same designer clothes he wore outside the studio, marked by splatters, frayed hems, and cigarette burns. It was a look that suggested not carelessness but a deliberate refusal to treat fashion as precious.

In doing so, Basquiat challenged the conventional divide between luxury and labour, making the act of destruction itself part of his visual language. His look has since been widely appropriated in both streetwear and luxury branding, used to evoke authenticity, rebellion, and edge.

Where Basquiat’s look was unruly and expressive in its rebellion, Andy Warhol’s was composed, minimal, and cool. His public persona was one of the most meticulously constructed in postwar art.

In the 1960s, he developed a signature look that was instantly recognisable: dark sunglasses, black turtleneck or striped T-shirt under a black leather jacket, blue jeans, and black boots. It was almost a rockstar uniform, punctuated by the silver wig that became his lifelong visual hallmark. The effect was one of calculated rebellion, cool detachment, and a hint of menace. This remains the archetype of the black-clad New York artist.

By the 1970s, the look evolved, but always with intention. The leather gave way to Oxford shirts, repp ties, navy Brooks Brothers blazers, and clear-framed glasses. It was a deliberate shift that mirrored his rise from avant-garde provocateur to established art-world figure. Only the jeans stayed.

The result was a subtly subverted preppy look. Warhol understood that it was often more powerful to tweak the standard than reject it outright. He had a rare sense of how superficial things could carry meaning. As he once put it, “I am a deeply superficial person.”

While Andy Warhol cultivated a distinctly American look, David Hockney has long expressed a refined but unmistakably English sensibility, one that carries a touch of gentle subversion. It’s no wonder he is such a consistent reference for menswear brands.

Throughout his career, he has consistently favoured vibrant pastel tones, mismatched patterns, and bold colour combinations that echo the palettes of his own paintings. His wide-rimmed, round glasses and slightly rumpled appearance suggest he dresses out of creative enthusiasm rather than concern for polish.

Hockney’s attire has remained remarkably consistent since the 1960s. He treats dress much like his paintings, layering colour and texture with instinctive flair. His visual sensibility radiates through his wardrobe, offering a kind of wearable optimism that has made him a lasting source of inspiration in both art and fashion. He embodies the playful and expressive individualist, the eccentric dandy.

All of these artists were, or are, remarkable dressers, far more nuanced than the clichéd versions often recycled by the fashion industry. Yet it is precisely this recognisability that makes them so valuable as marketing figures. Their styles are easily distilled into visual shorthand and redeployed across campaigns, editorials, and moodboards. They offer familiar cues that brands can borrow to signal cultivated depth, rebellion, or sophistication.

Some artists are exceptionally skilled at navigating the interplay between appearance and identity, whether through instinct or deliberate construction. In certain cases, the connection between their style and their work becomes so pronounced that the two are nearly impossible to separate. Their clothing becomes part of their artistic mythology.

It is difficult to imagine Joseph Beuys without conjuring the image of the felt hat and fishing vest. Beuys infused every aspect of his life with personal symbolism, weaving together biography and fiction. His appearance was an extension of his conceptual work, breaking down the boundary between performance and daily life. In a sense, the artist himself became the medium.

Marcel Duchamp, by contrast, projected a different kind of authority. Most photographs show him as the detached intellectual, dressed in a dark suit and tie, a scarf casually looped around his neck, a pipe in hand.

His reserved elegance and piercing gaze gave him an air of quiet superiority, a presence that allowed him to expand the boundaries of art without losing credibility. Seen from this angle, his cross-dressed alter ego Rrose Sélavy appeared less a provocation than a philosophical gesture, carried out with the same calm precision.

Ultimately, the way artists dress reveals more than aesthetic preference or practicality. It speaks to the subtle ways identity is constructed, contested, and performed, both in private and in public.

As cultural figures, artists have become visual touchstones for fashion’s own projected ideals. Yet behind each iconic look lies a personal negotiation between the demands of the studio, the expectations of the world, and the impulse to remain true to one’s work. For the artist, style is never just a matter of appearance but a continual balancing act between practice, performance, and the image they choose, hope to, or refuse to project.

For more from Philipp, see his piece on what colour theory can teach us about dressing

Related posts

- What artists wear, as projection and performance

July 30th 2025 – 9 CommentsRead More

- Yves Salomon: Interview in Paris

July 28th 2025 – 14 CommentsRead More

- New events: Casatlantic, J.Mueser, Subdial, pre-owned

July 25th 2025 – 19 CommentsRead More

Subscribe to this post

–>