Table of Contents

Working from a dock on St. Helena Island, S.C., on a sweltering day this summer, Ed Atkins pulled in a five-foot cast net from the water and dumped out a few glossy white shrimp from the salt marsh.

Mr. Atkins, a Gullah Geechee fisherman, sells live bait to anglers in a shop his parents opened in 1957. “When they passed, they made sure I tapped into it and keep it going,” he said. “I’ve been doing it myself now for 40 years.”

These marshes, which underpin Mr. Atkins’s way of life, are where the line between land and sea blurs. They provide a crucial nursery habitat for many marine species, including commercial and recreational fisheries.

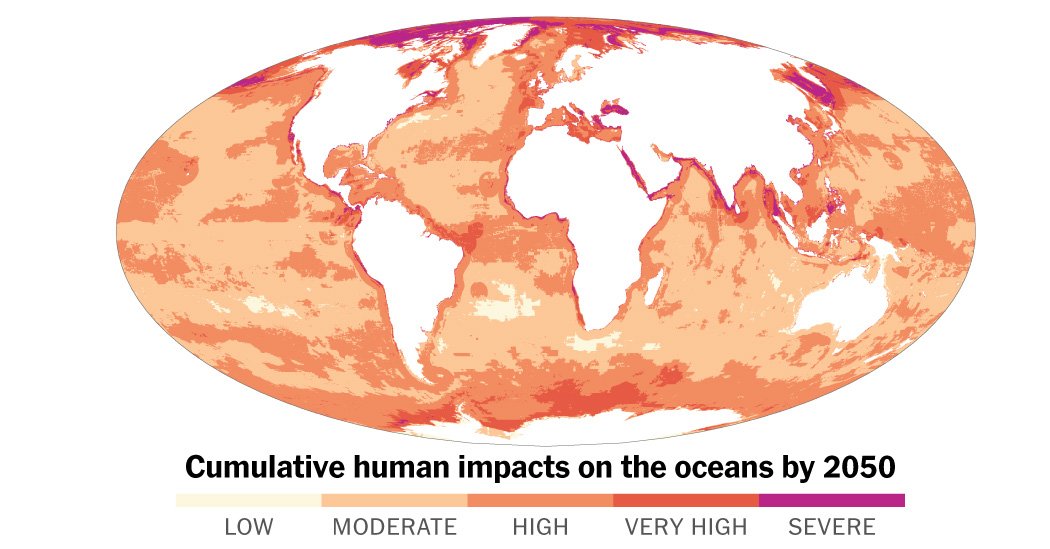

But these vast, seemingly timeless seascapes have become some of the world’s most vulnerable marine habitats, according to a new study published on Thursday in the journal Science that adds up and maps the ways human activity is profoundly reshaping oceans and coastlines around the world.

Soon, many of Earth’s marine ecosystems could be fundamentally and forever altered if pressures like climate change, overfishing, ocean acidification and coastal development continue unabated, according to the authors.

It’s “death by a thousand cuts,” said Ben Halpern, a marine biologist and ecologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and one of the authors of the new study. “It’s going to be a less rich community of species. And it may not be something we recognize.”

Among the other ecosystems at high risk are sea grass meadows, rocky intertidal zones and mangrove forests. These parts of the ocean, near shore, are the ones people most depend on. They provide natural defenses against storm damage. And the vast majority of commercial and recreational fishing, which together support more than two million jobs in the United States alone, takes place in shallower coastal waters.

There’s also an intangible cultural richness at stake. The culture of Gullah Geechee people like Mr. Atkins, a community descended from enslaved West Africans forced to work the rice and cotton plantations of the Southeastern coast, for example, is inextricably linked to fishing and the seashore.

“We have our own language, we have our own food ways, we have our own ecological system here,” said Marquetta Goodwine, the elected head of the Gullah Geechee people and a leader in efforts to protect and restore the coastline. That distinctive culture, she said, depends on things like the oyster beds, the native grasses and the maritime forests that characterize the seashore and the scores of tidal and barrier islands here, collectively known as the Sea Islands.

“You don’t have that, you don’t have a Sea Island,” said Ms. Goodwine, who also goes by Queen Quet. “You don’t have a Sea Island, you don’t have Gullah Geechee culture.”

A Poorer Ocean

The new study tries to measure just how much various human-caused pressures are squeezing, shifting and transforming coastal and marine habitats.

The research began in the early 2000s, when widespread coral bleaching was raising alarm among marine scientists. In response, Dr. Halpern and his colleagues set out to map the parts of the ocean that were healthiest and least affected by humans and, conversely, which parts were the most affected.

The inherent challenge was comparing marine habitats, from coral reefs to the deep ocean floor, and their responses to different human activities and pressures, like fishing and rising temperatures, all on a common scale. They came up with what researchers call an impact score that’s based on a formula incorporating the location of each habitat, the intensities of the various pressures on that habitat, and the vulnerabilities of each habitat to each form of pressure.

Under the world’s current trajectory, the study found, by the middle of the century about 3 percent of the total global ocean is at risk of changing beyond recognition. In the nearshore ocean, which most people are more familiar with, the number rises to more than 12 percent.

That future will look different in different regions. Tropical and polar seas are expected to face more pronounced effects than temperate, mid-latitude ones. Human pressures are expected to increase faster in offshore zones, but coastal waters will continue to experience the most serious effects, the researchers forecast.

There are also countries that are considered more vulnerable because they depend more heavily on resources from the ocean: Togo, Ghana and Sri Lanka top the list in the study.

Across the whole ocean, scientists generally agree that many places will look ecologically poorer, with less biodiversity, Dr. Halpern said. That’s mainly because the number of species that are resilient against climate change and other human pressures is simply far fewer than the number of more vulnerable species.

The study found that the biggest pressures, both now and in the future, are ocean warming and overfishing. But the researchers most likely underestimated the effects of fishing, they wrote, because their model assumes that fishing activity will hold steady rather than increase. They also focused only on the species actually targeted by fishing fleets and did not include by-catch, the unwanted species swept up in gear like gill nets and discarded, or habitat destruction from bottom trawling.

The effects of some other human activities aren’t well represented either, including seabed drilling and mining, which are expanding quickly offshore.

Another limitation of the Science study is the fact that the researchers simply added together the pressures from human activities in a linear way to arrive at their estimate of cumulative effects. In reality, those effects might add up to more than the sum of their parts.

How individual stressors contribute to cumulative impacts

Even low-ranking global stressors can cause enormous damage to local ecosystems

“Some of these activities, they might be synergistic, they might be doubling,” said Mike Elliott, a marine biologist and emeritus professor at the University of Hull in England who was not involved in the study. “And some might be antagonistic, might be canceling.”

Even so, Dr. Elliott said he agreed with the broad conclusions of the new study. Scientists could argue about whether the cumulative effects of human activities will double or triple, he said, “but it will be more, because we’re doing more in the sea.”

“If we wait until we’ve got perfect data,” he added, “we’ll never do anything.”

‘Time to Scale It Up’

One of the benefits of such studies is that they can help inform better ocean planning and management, including initiatives like 30×30, the global effort to place 30 percent of the world’s land and seas under protection by 2030.

In South Carolina, one place that has already been set aside is the ACE Basin, a largely undeveloped 350,000-acre wetland on the state’s southern coast that is named for the Ashepoo, Combahee and Edisto rivers, which thread through it.

Riding a boat across the enormous basin can be disorienting. The world flattens as the sun beats down and salt marsh stretches in every direction. Almost everything is a vivid blue or green, like an abstract painting or a map come to life.

White wading birds dot the green marsh grasses, and occasional groups of gray bottlenose dolphins break the blue surface of the water.

Sometimes the dolphins corral their fish prey onto the mud and temporarily beach themselves for a meal, using the salt marsh islands like giant dinner plates. This behavior, called strand feeding, is rarely seen outside the Southeast.

On a recent visit, in one tucked-away corner of the marsh, something emerged from the mud at low tide: a wall, built with concrete blocks now nearly hidden by thousands of shells. They’re called oyster castles, and they look like something out of a storybook about mermaids.

The blocks were placed by volunteers from the Boeing assembly plant in nearby North Charleston. The effort was organized by the Nature Conservancy and the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources as part of a growing string of living shorelines projects, which aim to stabilize the coast using natural materials like shellfish and native vegetation, in South Carolina and beyond.

The oyster castles are meant to protect the landscapes behind them from erosion, sea level rise and storm surges. Scientists from the Nature Conservancy have been experimenting with a variety of methods for years, and are beginning to see results. Behind the oyster castles, which allow water to pass through and deposit sediment, mud had piled up significantly higher than elsewhere. And in the mud, marsh grass has taken root and grown tall.

“We’ve been testing and piloting things for so long, and now is the time to scale it up,” said Elizabeth Fly, director of resilience and ocean conservation at the Nature Conservancy’s South Carolina chapter.

In fact, the state’s oyster shell recycling program has now built small living shorelines at more than 200 sites, all with the help of volunteers, and often working with other groups, like the Gullah Geechee Nation. There’s a living shoreline taking shape at the Charleston wastewater treatment plant. Another at the entrance to the exclusive Kiawah Island Golf Resort. They’re at Marine Corps bases, at boat launches and at docks.

Many of these efforts are part of a sprawling network called the South Atlantic Salt Marsh Initiative, which includes the Pew Charitable Trusts, the Department of Defense, other federal agencies and state governments. The network spans one million acres of salt marsh across four Southeastern states.

Amid those efforts to reinforce and protect marine ecosystems, and as scientists work to better understand the pressures that are altering the oceans, people in coastal communities everywhere are already living changes large and small.

The day after Mr. Atkins demonstrated his fishing methods, the town of Mount Pleasant, S.C., 80 miles up the coast, held its annual Sweetgrass Festival to celebrate the region’s traditional Gullah Geechee baskets. Dozens of artists braved the heat in booths at a waterfront park, showing off and selling baskets woven from sweetgrass, bulrush, palmetto leaves and pine needles.

One artist and teacher, Henrietta Snype, displayed baskets made by five generations of her family, from her grandmother down to her own grandchildren.

Ms. Snype started making baskets at age 7. Now, at 73, she takes pride in upholding the tradition and teaching others the craft and its history. But she feels the world around her changing.

She said she had noticed the climate shifting for many years now. Big hurricanes seem to have become more frequent and seem to do more damage. And making baskets is harder, too.

Traditionally, the men in basket-making families went out into the dunes, marshes and woods to gather the materials they needed. But lately, Ms. Snype said, the plants have been harder to find. Sweetgrass is diminishing, and harvesters have trouble getting access to built-up and privately owned parts of the coastline.

“The times bring on a lot of change,” she said.

Methodology

Maps and table showing human impacts on oceans reflect estimates based on the SSP2-4.5 “middle of the road” scenario, which approximates current climate policy.